There’s arguably nothing more important to the resiliency of a community than a river. Besides providing drinking water, allowing for the passage of floods, and meeting other societal needs, rivers and the wide range of species that inhabit them influence the overall stream ecology. And the interaction of a river’s flow with the built environment, including bridge crossings and other types of infrastructure, affects traffic, commerce, emergency services and more.

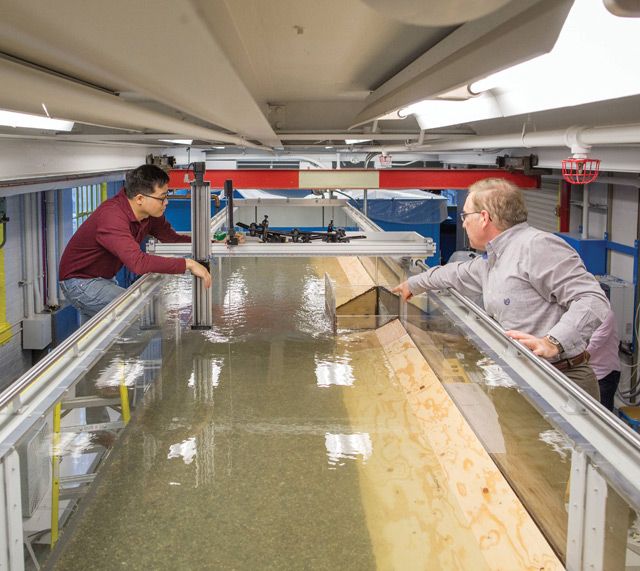

In Lehigh’s newly renovated Imbt Hydraulics Laboratory, Panos Diplas, the P.C. Rossin Professor and Chair of the civil and environmental engineering department, studies two river phenomena— scour and meandering—that have challenged engineers for centuries.

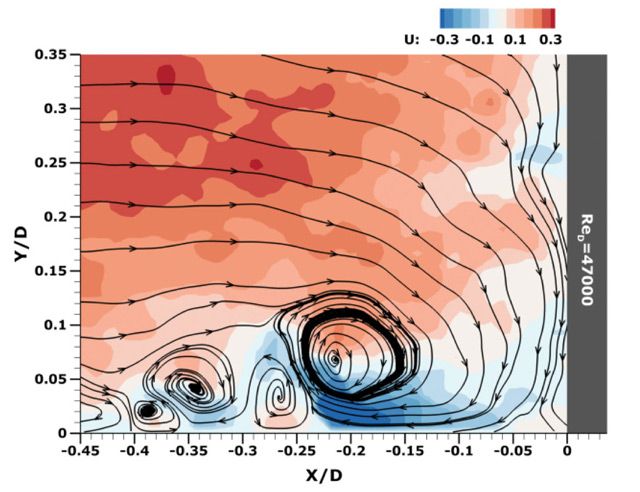

Scour typically occurs during major floods, when a river’s flow rises, kicks up sediment on the riverbed and transports it downstream. It is by far the leading cause of bridge failure in the United States.

“When sediment in the vicinity of a structure is mobilized,” Diplas says, “a scour hole forms where the structure meets the soil. This, in turn, can compromise the structure’s integrity.”

In an NSF project, Diplas and his group are studying the movement of sediment particles. With support from the National Cooperative Highway Research Program, they are attempting to determine the physical mechanisms responsible for scour development near structures. Their goal is to devise cost-effective scour mitigating measures that will allow bridges to withstand severe flow conditions.

Meandering occurs when rivers move and bend in seemingly random ways. It is a natural, healthy process, but scientists have not yet determined why rivers meander instead of following a straight path.

When a river meanders far outside of projections, says Diplas, a bridge built over a river can be isolated on a floodplain. It no longer performs optimally and can be compromised by an extreme event, costing money, time and even lives.

Human responses to meandering can upset naturally occurring conditions that sustain fragile river ecosystems, says Diplas. Fish populations have shrunk rapidly when humans manufacture unnatural conditions to counteract the effects of meandering.

Diplas takes a big picture approach to solving river-related problems and encourages students to look at water resource problems at the systems level.

“We tend to treat the symptoms rather than the disease,” he says. “If you try to fix a problem by simply putting a bandage on it, you can make it worse or create more problems in the future.”