In 1958, John W. Fisher ’58G ’64 PhD took a job as an assistant research engineer at what was the most ambitious road test of the time.

The American Association of State Highway Officials (AASHO) had built seven miles of a two-lane highway in a series of six loops in Illinois. The goal was to see how commonly used design methods held up against a barrage of heavy vehicles being driven by a rotating group of soldiers.

Fisher—then 27, and having recently completed his master’s degree in civil engineering from Lehigh University—took measurements on the 16 bridges included in the AASHO Road Test and checked for signs of wear and tear. Later, he helped carry out increasing load tests to make the spans fail.

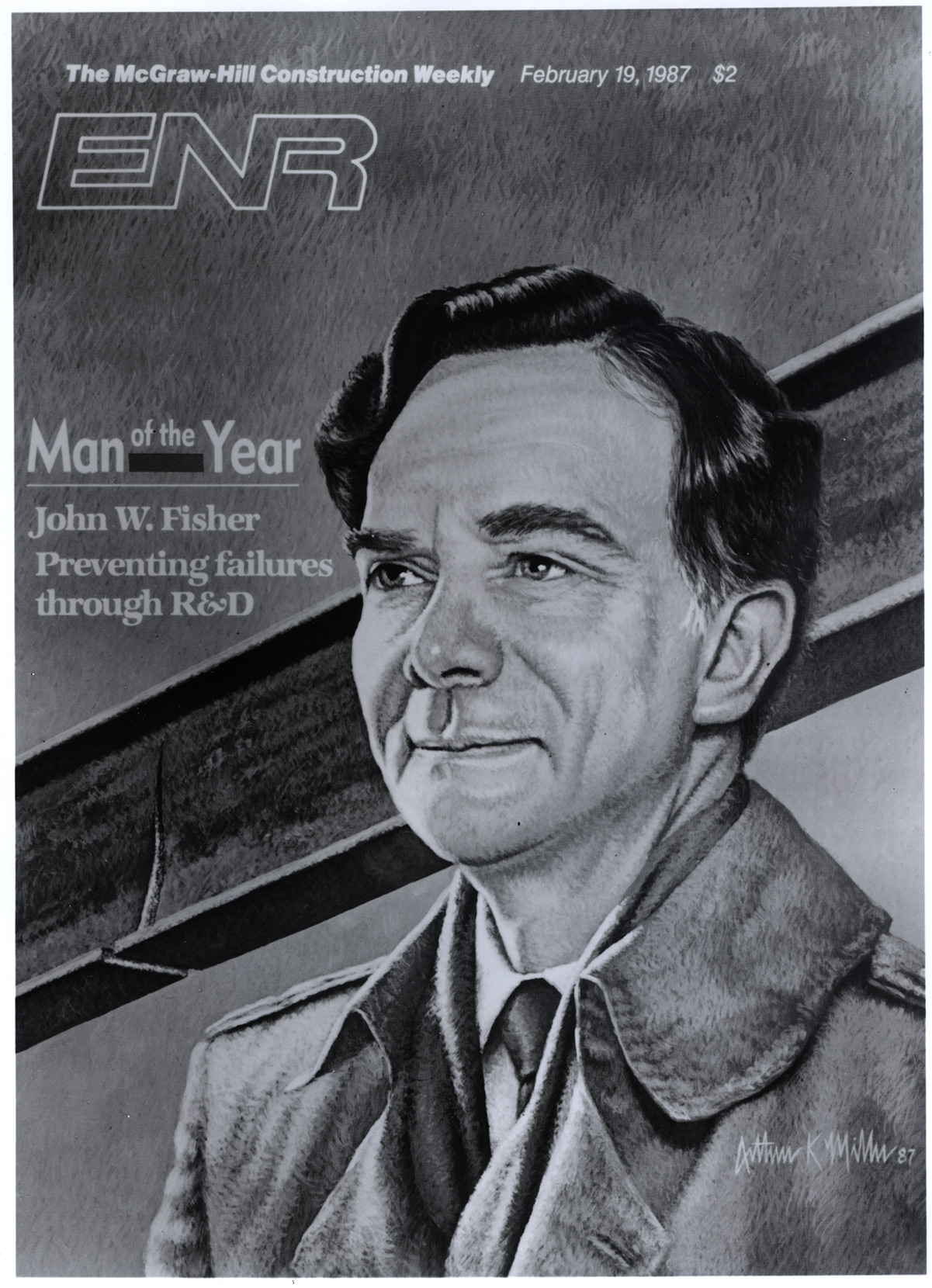

The experience was transformative. It would propel Fisher to be elected as a member of the National Academy of Engineers and a Distinguished Member of the American Society of Civil Engineers. It would set the stage for him to become one of Engineering News-Record’s “Top 125 People” in the construction journal’s history. And it would lead him to serve as founding director of Lehigh’s world-renowned Advanced Technology for Large Structural Systems (ATLSS) Engineering Research Center, drawing talented researchers and hundreds of eager students to take part in the center’s groundbreaking research.

“Cracking developed during those tests, and eventually turned out to be a major problem,” Fisher says, citing the failure of four spans that had to be rebuilt mid-testing.

Fisher theorized that fatigue design needed to be changed for bridge design and that testing should be done on life-size specimens.

“A lot of my research efforts grew out of that experience,” says Fisher, a former Joseph T. Stuart Professor of Civil Engineering.

Fisher looked back on his early career as he marked his 90th birthday on Feb. 15, 2021.

The milestone included a virtual celebration, held via Zoom, where about 20 of his former students and colleagues, logging in from California to Switzerland, shared stories and showed old photographs, including one of Fisher, magnifying glass in hand, looking for cracks in a bridge in western Pennsylvania.

“They all thanked Dr. Fisher for his mentorship and his influence on their lives,” says Sougata Roy ’01G ’05 PhD, who organized the gathering. Roy was Fisher’s last doctoral student and is now an associate research professor at Rutgers University.

Fisher is still leaving his imprint.

He remains active in professional organizations, is under two contracts to provide structural advice, and is called upon to lend his expertise, as he did with the 2001 collapse of the Twin Towers at the World Trade Center after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks.

“I am still interested in remaining involved in these issues,” says Fisher, who officially retired as a professor emeritus in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering in 2002, but has yet to fully step away from his work.

Interest in bridges started in the military

Fisher’s interest in bridges was forged as a second lieutenant with 4th U.S. Army Engineer Combat Battalion. He was assigned to supervise the building of emergency bridges in Germany to shore up defenses against the Soviet threat.

He was born in Scott City, Missouri, and joined the U.S. Army in 1951, dropping out of college after a year, partly out of the sense of duty instilled to him at age 10.

In 1941, Fisher’s family, which eventually grew to 11 children, was living in Hawaii while his father, Nevan, worked as a dredge master for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers at Pearl Harbor.

The family was getting ready for church on Dec. 7, when the elder Fisher looked out a window and saw a plane go down in a ball of fire.

“My dad said we were at war,” says Fisher. “I grew up then and there.”

Fisher left the military in 1953, joining his wife, Nelda, in St. Louis, where he earned his undergraduate degree in civil engineering from Washington University in 1956.

He headed to Lehigh for a master’s degree after hearing Lynn S. Beedle ’52 PhD, the esteemed late director of Fritz Engineering Laboratory, give a guest lecture. In the same way, Fisher’s expertise would later draw other bright minds in civil engineering to South Bethlehem.

Early research at Lehigh

After AASHO Road Test ended in 1961, Fisher returned to Lehigh and delved into doctoral research on high strength bolted connections, much of it tied to the needs of nearby Bethlehem Steel Corp.

In 1967, Fisher, then a faculty member, won his first big grant from the National Cooperative Highway Research Program to study the effects of weldments on the fatigue strength of steel bridges.

At the time, many engineers believed modern bridge design was so sound that it would prevent problems like cracking. Their thinking was based on the idea that if a structural detail withstood 2 million stress cycles, it would not fail at 5 or 10 million cycles.

But Fisher, skilled in computers, used a statistically based approach to his research, running specimens through stress cycles until they outright failed.

He proved that the fatigue limit was different for different details, meaning a specimen might not reach the breaking point until 20 million cycles.

“That led me to develop the concept of a stress range being the most important aspect,” Fisher says.

At first, his research ruffled the engineering world.

“But our findings resulted in the adoption, in the U.S. and most of the world, of comprehensive specifications for designing steel structures, particularly bridges for fatigue resistance,” he says.

The origin of ATLSS

As his grant continued into the mid-1980s, Fisher still wanted to test life-size specimens. But Fritz Lab, which was founded in 1909 and enlarged in 1954, did not have adequate space.

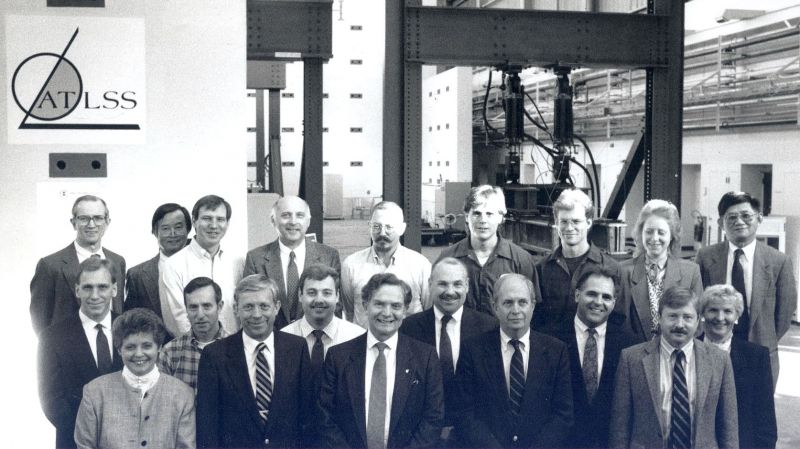

Fisher got his chance in 1987, when the National Science Foundation approved his proposal with Alan Pense ’62 PhD to establish the nation’s first Engineering Research Center (ERC) dedicated to studying large structures at Lehigh.

Winning the fiercely competitive grant, says Richard Sause, now director of ATLSS and Lehigh’s Institute for Cyber Physical Infrastructure and Energy (I-CPIE), “was one of the most significant achievements of John’s career.”

With Fisher at the helm, the Advanced Technology of Large Structural System Engineering Research Center opened in a former Bethlehem Steel research building on the Mountaintop Campus.

The facility, still one of the largest of its kind, features a 100-foot (30.5m) by 40-foot (12.2m) research floor with two rigid reaction walls, one standing 50 feet tall and the other stepping down incrementally from 40 to 20 feet.

The facility can generate multi-directional static and time-varying loads with the help of a computer-driven hydraulic power system, which operates at 3,000 psi (20.7Mpa) and 600 pgm (227 liters/min).

ATLSS allowed Fisher and fellow researchers to conduct tests on large-scale riveted bridge girders taken directly from bridges in the U.S. and Canada. Full-scale orthotropic bridge decks were also brought in from New York City’s Williamsburg Bridge and the Bronx-Whitestone Bridge.

“These tests simulated multiple lanes and took up at least half of the test facility,” Fisher says.

In one long-running study, ATLSS carried out tests under the U.S. Navy’s Fleet of the Future program, studying whether ships with double hulls would be better protected from punctures and fatigue.

To do so, a 36-foot-high section of a hull was brought in.

“We had a laboratory that allowed us to simulate a lot of the things we saw happening in the real world,” Fisher says.

Over time, research at ATLSS has evolved and expanded.

It now houses the Natural Hazards Engineering Research Infrastructure (NHERI) Lehigh Real-Time Multi-Directional Experimental Facility to study the impact of earthquakes and natural disasters on structures. In January, the NSF renewed funding for the facility for another five years with a $5.3 million grant.

Today, about 80 people, including students, research associates, staff, faculty members, and visiting researchers can be found conducting research at ATLSS, which also includes Fritz Lab.

“The whole thing is a result of Dr. Fisher,” says ATLSS Administrative Director Chad Kusko ’01 MBA ’02 PhD.

In demand

As a result of his groundbreaking research, Fisher was in demand to help write new building and design codes in the U.S. and abroad.

Fisher appeared before Congress and state legislatures to push for increased funding for research, development, and infrastructure improvements.

With site visits the hallmark of his pedagogy, he traveled around, teaching engineers how to look for signs of fatigue and fracture.

In a testament to his stature, Fisher was called upon to offer his insight on why bridges, highways, buildings, buses, and windmills were showing signs of fatigue or had collapsed with catastrophic results.

Over the years he would consult on 238 engineering issues, including the collapses at the Hyatt Regency Hotel in Kansas City (1981), the Mianus River Bridge on Interstate 95 in Connecticut (1983), and the Daniel Hoan Memorial Bridge on Interstate 794 in Milwaukee (2000).

Backed by federal grants, Fisher inspected the sites and then returned to Lehigh to re-create the conditions that led to the failures.

That also happened after the 1994 Northbridge–Los Angeles earthquake, when buildings—thought to be tremor proof—developed fractures at welded joints at beam-to-column connections.

The culprit was a weld metal known as E7OT-4. Testing at ATLSS showed it was brittle.

“You should never use this kind of material,” Fisher told The Los Angeles Times in December 1996. “We should ban its use.”

As a result of research by Fisher and others, Los Angeles passed such a law.

Above, right: Notes on the Williamsburg Bridge, from The John W. Fisher Papers (Lehigh University Omeka, https://omeka.lehigh.edu/items/show/1735)

Respect from students, colleagues

Respect from students, colleagues

Early on, Fisher’s reputation as a trailblazer reached new engineering graduates.

Among them was Karl Frank ’69G ’71 PhD who headed to Bethlehem in 1966 after hearing about Fisher from Lehigh civil engineering alum Jean-Claude Badoux PhD ’65, then a professor at the University of California, Davis.

Right away, Frank says, Fisher encouraged his interests, allowing him to add a facture mechanics analysis of beam fatigue tests to his master’s thesis at the tail end of the program.

“That was a whole new field of study,” says Frank, who would go on to help the Federal Highway Administration develop the fracture control plan for steel bridges before becoming a professor at the University of Texas at Austin and later a chief engineer with Hirschfeld Industries.

But Frank says Fisher could be no-nonsense, once leaving him behind on a trip to Philadelphia to inspect the Walt Whitman Bridge when he was late. Frank raced to the site on his motorcycle. When Fisher saw him, he made no mention of what happened and simply asked, “Did you just start working?”

At right: Fatigue Study Photograph of The Walt Whitman Bridge, from the papers of John W. Fisher. (Lehigh University Omeka, https://omeka.lehigh.edu/items/show/4076)

Duncan Paterson ’01G ’04 PhD heard of Fisher’s expertise soon after arriving at Lehigh and quickly signed up for one of his courses.

“You were learning about fatigue and fracture directly from the source. It was a blessing to this day,” he says.

Fisher was quiet and patient, preferring to guide from afar, says Paterson, now bridge instrumentation program lead and bridge section manager at HDR in Cincinnati.

“He let me make my mistakes. And then we talked about why things happened the way they did,” says Paterson, who worked on the Fleet of the Future project.

Alain Nussbaumer ’94 PhD is among six students who studied under Fisher through his relationship with the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL).

In 1974, Fisher went to Zurich, Switzerland, to help write steel specifications at the invitation of Konrad Basler ’59 PhD. He then returned to Lausanne in the 1980s during a sabbatical to write a book, Fatigue and Fracture of Steel Bridges: Case Studies. He was awarded the distinction of docteur honoris causa by EPFL in 1988 and was elected a corresponding member of the Swiss Academy of Engineering Sciences in 1989.

Nussbaumer, now a professor at EPFL, says Fisher’s mentoring went beyond the lab.

During Nussbaumer’s first semester, when he was new to America, Fisher invited him and other international researchers to his house for Thanksgiving dinner.

“He was welcoming,” says Nussbaumer, who shared a photo of the occasion during Fisher’s online birthday celebration.

The work being done at ATLSS also attracted faculty members, including Sause, who arrived at Lehigh in 1989 to become an assistant professor and succeeded Fisher when he stepped down as ATLSS director.

Fisher treated his fellow academics with respect and didn’t push his opinions even though he certainly had the expertise to back them up, says Sause, who is the Joseph T. Stuart Professor of Structural Engineering.

“He’s very measured and thoughtful in terms of his input,” Sause says. “I think it’s really effective in a research environment.”

Fisher’s expertise and graciousness resonated throughout his home department as well, says Arup SenGupta, a long-time colleague and former chair of the civil and environmental engineering department and head of its environmental group.

“What sets John apart from others is his professional and personal humility,” says SenGupta, a professor of both CEE and chemical and biomolecular engineering. “He’s an extraordinary individual who defines our institution. He’s truly the embodiment of everything good that Lehigh stands for.”

A living legacy

Throughout the course of his fruitful career, Fisher has accumulated a list of accomplishments that runs over 50 pages, and includes 305 books and papers and dozens of awards and recognitions. including the Roy W. Crum Award for outstanding achievement in transportation research, from the Transportation Research Board, part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

In 2000, he received perhaps his most distinguished honor—the John Fritz Medal. The award, named for the iron and steel industry pioneer who designed and funded the construction of Lehigh’s Fritz Laboratory, has been presented annually since 1902. It is widely regarded as the highest honor one can achieve in the engineering profession.

Clearly, Fisher has reached the top of his field, yet he is far from finished. Before the coronavirus pandemic struck in March 2020, he continued to come to work at ATLSS from time to time.

Clearly, Fisher has reached the top of his field, yet he is far from finished. Before the coronavirus pandemic struck in March 2020, he continued to come to work at ATLSS from time to time.

He keeps up with his emeritus memberships in the American Institute of Steel Construction Specification Committee and the Steel Structures Committee of the American Railway Engineering and Maintenance of Way Association.

Fisher is under contract to provide consulting work to Ohio-based American Electric Power and the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority in New York City.

“He’s a knowledgeable person that people will contact,” Sause says. “His opinion is still highly valued, especially in a situation where there is a problem.”

In addition, Fisher is still active at Fritz Memorial United Methodist Church in Bethlehem as a lay leader and financial chair.

Then there are his and Nelda’s 4 children, 10 grandchildren, and 7 great grandchildren.

The couple celebrated 69 years of marriage in October 2021.

“I try to do as much as I can at my age,” he says.

As he ponders his career at 90, Fisher says developing the ATLSS Engineering Research Center is among his proudest achievements.

But when it comes to his legacy, he says something stands out more.

“I would like Lehigh to remember me through my students, particularly my graduate students and postdocs who worked with me on all of my research and made it a success,” Fisher says. “That would be foremost.”

—Katherine Reinhard ’85G is a freelance contributor for the P.C. Rossin College of Engineering and Applied Science