ER doc, healthcare systems engineer David Adinaro ’88 ’15 M.Eng. leads Secaucus Field Medical Station taking stress off NJ hospitals during pandemic

Earlier this year, Dr. David Adinaro was in between jobs after leaving New Jersey’s St. Joseph’s Healthcare System, where he’d spent the past 17 years. His short-term plan was to return to clinical emergency medicine, where he’d started his career. But before those plans could materialize for the former chief medical officer, COVID-19 began to bear down on the region.

Then the phone rang.

“It was the New Jersey Department of Health calling me, pretty much out of the blue, asking if I’d be willing to be the chief medical officer of this thing they were in the process of building,” says Adinaro, who is a graduate of Lehigh’s Healthcare Systems Engineering (HSE) professional master’s program. “I kind of said ‘yes, I’ll help’ before they actually explained what it was, though I wouldn’t have changed my mind anyway.”

Adinaro is now one of two executives at the helm of the NJ Field Medical Station Secaucus—the Meadowlands-Exposition-Center-turned-field-hospital that’s caring for recovering COVID-19 patients to relieve pressure from hospitals across northern New Jersey. With support from the state’s National Guard, Office of Emergency Medical Service, and additional partners, the 250-bed facility was built in March—in a little over a week. Approximately 275 patients have been treated and released since the FMS opened on April 8.

“I’m an emergency physician, so it will always feel like I’m not doing enough unless I’m in the absolute chaos of the ER,” he says. “But realistically, by getting as many patients as we can out of these hospitals, we’re making it possible for doctors and nurses to have better patient ratios, so they can focus on the sicker patients. And we’re getting some of the less sick people away from an environment where it’s chaotic. All of that has been wonderful.”

Back in April, Adinaro took time out of a typically hectic day—escaping momentarily to his car where he could silence his radio and shed his mask—to talk with the Rossin College about what it takes to run a field hospital in the time of coronavirus, and how his education and experience have prepared him for the job at hand.

Could you describe how the field hospital got started and what it’s like working there?

When I got to the Meadowlands Exposition Center, 250 cubicles had been erected to serve as patient rooms. Over the next eight days, we found staff, got radiology and lab support, and gathered all the equipment you need to be a stripped-down community hospital.

We are taking care of the “COVID convalescing.” Picture people who are sick enough to be in the hospital but are in the last three to seven days of their hospital stay. Most are between the ages of 45 and 75, though we’ve had people up to 96 and as young as 25, and all of them, almost exclusively, require oxygen.

Setting up oxygen was one of the initial challenges, and a bit of an engineering feat. Hospitals have sophisticated medical gas systems and big tanks of liquid oxygen. Here, we have to supply all of our oxygen through many heavy, smaller steel tanks. If we were an army, the ammunition for this place would be oxygen, because nearly 100 percent of our patients start out needing it. It is the one thing for which there is no substitute.

The good news is that we’ve encountered only seven patients with needs we couldn’t provide for and who had to go back to another facility. We are also equipped for anything critical that could happen. Besides being the chief medical officer, initially, I was the only emergency physician on staff to provide support if somebody would have an airway issue. Now, at nighttime, we have a paramedic crew here so I can sleep at home and not worry about that. We are essentially a small community hospital—without a lab, ICU, ER or OR—but we basically do everything else.

We have nurses and physical therapists, we can do outpatient labs, we can do x-rays. We have social workers. Most importantly we were provided a 25-person medical contingent of New Jersey Army and Air National Guard, who were key to our initial success.

We have nurses and physical therapists, we can do outpatient labs, we can do x-rays. We have social workers. Most importantly we were provided a 25-person medical contingent of New Jersey Army and Air National Guard, who were key to our initial success.

I was just talking to a plastic surgeon who’s working as a doctor here. I have a husband-and-wife combo who are a pediatrician and a spine surgeon. My main night guy is a vascular surgeon who just does outpatient vein procedures. There aren’t a lot of elective surgeries going on right now, so these doctors are coming and working here. We also have a lot of physician assistants and APNs [advanced-practice nurses]. But none of these people were practicing hospital-based medicine just a few weeks ago.

If we were talking movies, I’d say this place is a combination of a little bit of The Magnificent Seven, a little bit of The Dirty Dozen, a lot of Ocean’s Eleven, and then pick whatever 1930s Judy-Garland-Mickey-Rooney-we’re-putting-on-a-show-in-the-barns-film. That was the initial feel of this place, though it’s changing now, with policies and procedures in place, doctors doing rounds. But it is actually far harder than how I’m describing it. Consider all the elements of a hospital that you have to reproduce or scale down. At St. Joe’s, I’d spent the last five years getting the network off of paper and into a purely electronic system. Now, I’m running a hospital that is completely on paper. Think about that.

We’re practicing least-common-denominator, commonsense medicine. But there are just some things you have to do right. We have to be prepared for an emergency. We have to have PPE—personal protective equipment—and a lot of it to keep everybody safe. And we also need to know what to do if a staff member is sick, what to do if somebody has a needle stick. Just like in a normal hospital, those things have to work from day one.

It sounds like you are doing a little bit of everything. How would you describe the role of a CMO in a situation like this?

There are two executives running this FMS—me, the chief medical officer, and Patti Drabik, the chief nursing officer—where a hospital might normally have five to seven executives. Essentially, I’m in charge of anything medical. Provider relations, screening of the physicians, troubleshooting, any patient issues that come up. I’m working with the physicians to establish some cohesiveness in our approach. I’m making sure we’re prepared for emergency response and have everything that the physicians need care for patients.

Then, I have some operational duties that a CMO normally wouldn’t. I’ve taken on responsibility for all the respiratory therapy and oxygen supplies. I’ve spent a lot of time working with the respiratory therapist and calculating how much oxygen we need on a daily basis. What does that translate to in terms of portable tanks? And by portable, I mean they weigh 140 pounds each! How much oxygen tubing? How many regulators and these things called mutilators that can supply oxygen to up to eight patients at a time. There’s a little bit of engineering and a lot of math, which is not a normal CMO type of thing.

I also spend a lot of time interacting with the National Guard command and the Department of Health. And since all of our patients are coming from other hospitals, it’s kind of like a call-in radio show. I’m joking, of course, but from 9:30 to 11:30 a.m. and from 4 to 6 p.m. every day, I’m on the phone with our transfer center. They connect me with half a dozen hospitals at any given time. And then we’ll talk about their patients and discuss which ones we’re going to accept, and which ones we can’t. For example, we don’t take pregnant patients here. We can’t take a patient on dialysis. But we can handle the other general health concerns of most people recovering from COVID.

Caring for ‘COVID convalescing’ at NJ Field Medical Station Secaucus

How have your experiences prepared you for this job?

Having been an emergency physician for a long time, I’m used to a less well-defined environment. I also have a background in large projects: The scale of what we’re doing here isn’t really different from building an electronic medical record system for an entire hospital system. What’s different is we’re operating with many fewer people in a very, very short period of time. We’ve probably made decisions in the first eight to 10 days that normally would have been made over four to six months, if this were an EMR system implementation. But having project management expertise, knowing how to work with people from different backgrounds, being familiar with the incident command structure of the state police and their resources, and understanding what is the bare minimum needed to run a hospital have all prepared me for this job.

Where does your experience in engineering tie in?

A lot of what I’m doing is pure engineering, or troubleshooting on the systems side. You’re troubleshooting constantly where the rate-limiting steps are. Getting the hospitals to know what patients you’ll take. Then arranging for the patients to show up, and making sure they’re not all arriving at the same time. And then once you get them here, how do you get them home again? These are all steps in the system, and if there’s a failure at any point, it backs up everybody else in the flow. So, there is a fair amount of systems engineering and figuring out how you can safely get to the easiest, fewest number of steps possible.

We need to make it easy for the hospitals. If I asked for a complete medical record on every single patient before we’d even talk to them, they’d never send me a patient. We know they are so busy. We’re here because hospitals in Northern Jersey are bursting at the seams with people who are in danger of dying. And our job is to take the least sick of all those people and unburden the hospitals, doing it in a safe way with a properly trained team of professionals.

How do you measure success?

We’re getting a steady stream of patients, and our staff are coming back day after day. We have a very dedicated bunch of people who haven’t been together all that long. But the other day were able to have our first ice cream social for the staff. We’re considering having therapy dogs come one day and working on ways to keep up morale, because although these patients are relatively healthy, everybody’s working in a very austere environment.

Those working on the floor with patients are wearing their normal clothing, usually scrubs, plus an impregnable gown, plus an N95 mask, plus a surgical mask, plus an eye shield. And you’re in that for 11 hours of your 12-hour shift. You’re working in a new place, sitting on metal chairs with tables like you’d have at a picnic. You’re working on paper. The patient rooms are essentially 10-by-10 cubicles, with a curtain on one wall. There’s electricity, a lamp, a camp bed, pretty good Wi-Fi, another metal chair, and a little table that holds some of the patient’s belongings and gives them a place to eat dinner.

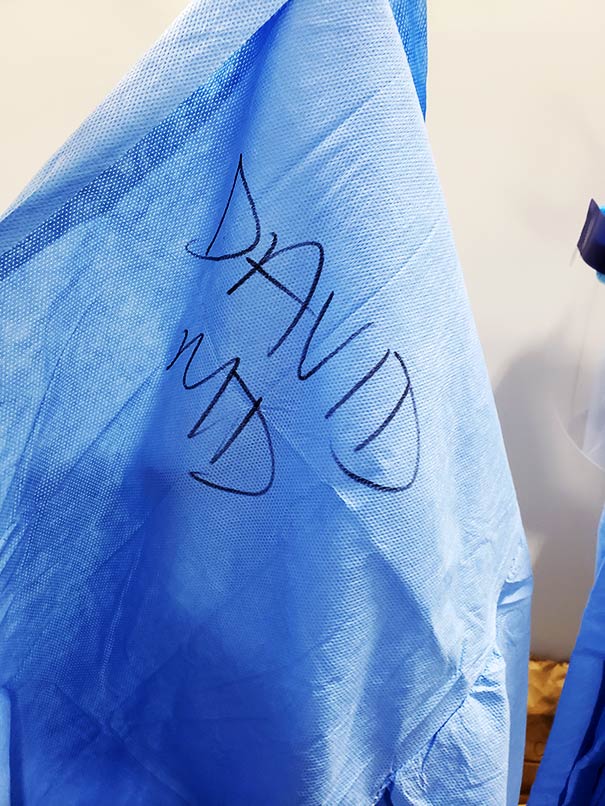

This is not a very posh place and it’s designed to be very temporary. We’re not going to have patients for weeks at a time here. But this is where the staff is working. And since we’re all new here, we’ve made it a tradition to write our names on our gowns. So, I would write “David” and “MD” across my chest with a marker on my blue gown on and have somebody write it on my right shoulder on the back. You can’t recognize people in all of this PPE, so it helps everyone know who everybody else is.

It seems like you’re helping develop a sense of community.

The funny thing is that the sense of community is unrelated to anything we’ve done. In these situations, you build the skeleton and then the people who are working flesh it out and make changes that are almost always for the good. They adapt your policies and procedures and guidelines so that they actually work. You can’t be out there the entire time and control them. I mean you put 20 people into a place and you give them some roles and they start figuring out how to do it. And then people will say, “well, this is how we do things here,” which is fascinating because this “here” didn’t exist three weeks ago.

My goal over the next couple of weeks will be to spend as much time as I can out on the floor. I have a step counter on my phone. During the first week and a half, I was probably getting between 2,000 or 3,000 a day. I was holed up having meeting after meeting while everybody else was setting up. The past three days, I’ve done over 9,000 steps. That’s a good sign: I’m on the floor more now and interacting with people while they’re working.

What do you see in the future for this field hospital?

At the beginning, we were building this thing because the hospitals were overwhelmed and we didn’t know if the curve was going to bend. When this place was originally conceived, it was supposed to be for non-COVID patients, to relieve stress on hospitals while they took care of COVID patients. By the time we were up and running, there were almost no non-COVID patients in hospitals. So, we switched gears and are focused on helping hospitals that are still overwhelmed.

At some point, these hospitals will need to resume treating people with other medical problems. As a society, we put a hold on elective surgeries—everything from tummy tucks to heart bypass surgery. People waiting for heart surgery are not getting healthier. In our area there’s not going to be some opening day where everybody just gets to go out and life is back to normal; medicine will come back in stages. So, I think our second act will take place when hospitals want to start bringing in patients who are non-COVID.

Another interesting idea coming from our state leadership is that we’re going to need places where people can be quarantined if they can’t self-isolate at home. Say you test positive for COVID, but you’re living with your 90-year-old grandfather. We need to get you out of the house and away from him. Places like this could be an alternative, particularly for people who have existing medical problems that need management.

So, while we are focused on the short term, there are scenarios where facilities like this could remain active for an extended period. Also, we will need to prepare for the future. A future that could include a combined COVID and influenza season next winter.

Interview by Katie Kackenmeister, assistant director of communications, P.C. Rossin College of Engineering and Applied Science

Photos courtesy of Dr. David Adinaro