The goal of many researchers is to make an impact. But too often, their work gets stuck in the narrow confines of their lab and respective academic fields and fails to influence the real world. As a result, fundamental research ends up falling into what’s known as the “translational gap.

The goal of many researchers is to make an impact. But too often, their work gets stuck in the narrow confines of their lab and respective academic fields and fails to influence the real world. As a result, fundamental research ends up falling into what’s known as the “translational gap.

“We’re supposed to be taking basic research and delivering it to society in the form of something useful,” says John Coulter, a professor of mechanical engineering and mechanics and the Rossin College’s senior associate dean for research. “But there are a lot of reasons for why that doesn’t always happen.”

Those reasons tend to fall under a lack of funding and support—and insufficient connection to users in society.

“It’s not uncommon for us to present our work at conferences, and afterward, hear from members of industry saying that while they love what we did, it doesn’t quite solve their problems,” says Coulter. “In those situations, it’s clear that if we’d worked with people like them from the beginning, we could have conducted our research more efficiently, and ultimately, more effectively.”

Forging those connections is at the heart of a proposal put forth last year by an interdisciplinary, university-wide team led by Coulter. In December, the National Science Foundation granted Lehigh a four-year, $6 million award through its Accelerating Research Translation (ART) program. The goal, according to the NSF, is to increase the scale and pace of advancing academic research into solutions that benefit and serve the public.

The 16-member team behind the proposal represents all five Lehigh colleges and includes four co-principal investigators and 11 senior personnel.

“Specifically, we’re talking about building capacity and infrastructure at all stages of the process,” says Coulter, “so that research is conducted in a way that’s quicker and targets real problems that people care about.”

The award will help Lehigh speed up and scale its research activities in engineering, health, biological sciences, humanities, business, education, and myriad other areas to generate products and services for the general good. Lehigh will also train graduate students and postdoctoral scholars in translational research and commercialization pathways.

Three paths to impact

Three paths to impact

“When it comes to translating research, NSF is targeting three pathways,” says Coulter. “The first is venture creation, meaning startups spawned by faculty and/or students.”

The second, he says, “is delivering our research more quickly into the hands of established companies.” That could be a company wanting to license a patent and sell products based on science that originated at Lehigh.

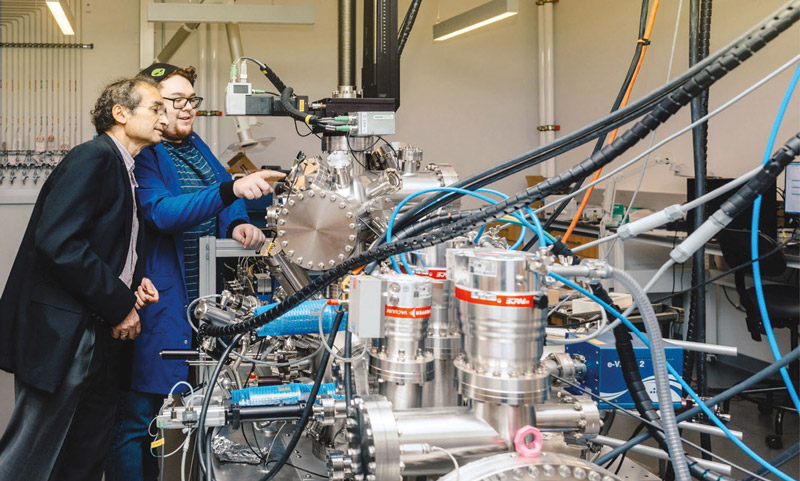

Another example, he says, is Lehigh’s Pasteur Partners PhD (P3) Program, in which doctoral students partner with industry to identify—and solve—real-world problems. Materials science and engineering professor Himanshu Jain, the T.L. Diamond Distinguished Chair in Engineering and Applied Science, is the key architect of the P3 model and a member of the ART leadership team.

“ART will help those students enrolled in the P3 program to further align their research for the benefit of society,” says Jain. “It will also serve as a new tool for recruiting superior graduate students.”

Ultimately, says Coulter, the idea is that students like those in the P3 program, whose research has been advised by both faculty and by industry partners, will go on to work for those industries. “And that research follows the student to that company,” he says, “which is very effective translation.”

The third translational area NSF is targeting is social impact.

“Some of the research we do within academic institutions isn’t intended to have economic value. Think of a piece of open-source software, for example, that’s useful to the world. It doesn't create revenue, but the impact is huge.”

To better help graduate students, postdocs, and faculty get their work onto one of those three impact pathways, Lehigh has to flex its academic muscle. Coulter explains his team’s vision using the metaphor of a gym.

“We want to create a campus ecosystem that provides the necessary capacity and infrastructure—the space, the equipment, and the expertise—for successful research translation,” he says. The program will offer an experience akin to a “personalized, total-body workout,” with educational and training opportunities focusing on building skills and nurturing an entrepreneurial mindset. Faculty members with related experience (such as Coulter, who holds multiple patents, including two issued in the past year) and external partners will serve as the trainers and coaches. And the cross-college team will strive to create a diverse, inclusive, accessible community that breeds innovation and sparks a shift in the university’s academic culture.

“We will optimize, incorporate, and enhance diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility in every piece of this ecosystem,” says Coulter. “And we’ll have regular assessment and continuous improvement of that system. Whenever we put a new policy on the table, there will be a team of people ready to vet it, and ensure that it embodies those values.”

Demystifying venture creation

Demystifying venture creation

To start and scale a successful company, first, you have to believe you can do it, and then, you need the skills to pull it off.

“The curriculum in Lehigh’s Technical Entrepreneurship graduate program offers a hands-on, industry-based, immersive educational approach to developing entrepreneurial knowledge, attitude, and skills, and this pedagogical approach will be utilized in the ART program,” says Michael Lehman, faculty director of interdisciplinary Technical Entrepreneurship (TE), a professor of practice in the mechanical engineering and mechanics department, and the ART team’s education and training lead.

“Our goal with ART is to immerse emerging innovators—regardless of their educational background and experience—simultaneously into both technical product development and entrepreneurial venture creation,” says Lehman, who has training as both a medical doctor and an MBA. He and his colleagues are adapting the TE curriculum to accommodate the rigorous demands of those pursuing translational research.

“What we’ve learned from past doctoral students is that a three-credit elective doesn’t necessarily work with their schedules,” he says. “So part of the ART grant will be utilized to develop flexible one-credit modules, ultimately offering 18 distinct, yet interrelated, topics.”

Those modules will cover subjects including customer discovery and problem validation; the power of diverse teams; financing R&D to commercialization; business models for translating tech; and effective professional communication. A current summer TE course on intellectual property will be offered in two separate one-credit modules—one on core IP skills, and one on IP strategy.

“These are interactive workshops with practical application,” he says. “Students will be using databases available through Lehigh to map their industry’s intellectual property landscape. They will engage with industry associations to craft effective partnerships. And they will develop a venture pitch, present it, get feedback, revise, and iterate.”

Ensuring the university community can access this kind of training is critical. The lack of understanding around new venture creation is one of the roadblocks to translational research. For academics so well versed in every nuance of their subject matter, stepping outside of it can be uncomfortable. There’s a tendency, says Lehman, to equate proficiency with deep knowledge. And when you consider just how many aspects there are to learn about when starting a company or translating an idea into global social impact, the prospect can be daunting.

“Many doctoral students and faculty have worked on technologies that could be commercialized,” he says. “But to create a new venture, you also need to learn about product development, design, financing, licensing, scaling, etc. It can be overwhelming. The goal is to get them comfortable with the idea that they don’t have to also be an expert in all those areas. But they do need to understand how they are all essential components that have to be addressed, either by themselves or by someone on their team.”

And participants don’t have to jump into all those areas at once. The modules are meant to provide a way to test the waters of potential.

“Someone may wonder, Is it reasonable to even think about commercializing my research? Well, there’s a module on feasibility analysis that could help them consider their research in a different way,” says Lehman. “Another might say, ‘I think I’m onto something, but I know nothing about sales or acquiring customers or negotiating.’ That person could take a related module to boost their confidence to take the next step.”

A paradigm shift

A paradigm shift

The kind of big changes being promoted by an effort like ART will require a simultaneous shift in institutional culture.

“Historically, PhD training has meant preparing a student to teach courses at any level, and training them to do cutting-edge research,” says Hannah Dailey, an associate professor of mechanical engineering and mechanics. “But changes in industry now require that people go beyond a deep, technical understanding of their subject area. Employers are looking for people who also understand the innovation ecosystem and have leadership potential. It’s not just about the science, it’s about knowing what it takes to bring discoveries to market. We want students and faculty who are doing research to be thinking about translation from day one.”

Dailey will lead that effort as coordinator of the “ART Ambassadors,” and as co-leader of the group focused on culture change at the university. ART Ambassadors, comprising faculty and students at different stages of research translation around campus, will help foster engagement, connection, and dissemination at the local, regional, and national levels of the many ways in which ART is transforming how research is done at Lehigh. They’ll also help facilitate the culture change necessary to fully embrace an ethos in which research translation is rewarded and valued and create an environment where researchers are excited and empowered to pursue the translational possibilities of fundamental work.

Such a transformation will require—among other things—changes in tenure, promotion, and evaluation processes.

“Right now,” says Coulter, “if you’re a junior faculty member trying to get tenure, you might be hesitant to start a company. And that’s because you think your colleagues will vote against you, believing your company will take up too much of your time. Well, what if starting a company becomes something that helps you get tenure?”

He says people such as Dailey—who started her own medical device company more than a decade ago—will also serve as mentors.

“Think of these people as coaches,” he says, returning the gym metaphor. “They’re people within our ART team, as well as from other areas inside and outside the university, who have venture creation experience, industry experience, intellectual property and patent experience, social impact experience. These coaches are going to help students and faculty identify the particular skill or skills that they’ll need to improve to work toward the goal of research translation. There’s really nothing quite like knowing a group of people who are starting or who have already launched companies when you’re trying to learn how to start one yourself.”

Building an innovation ecosystem

Building an innovation ecosystem

Finally, ensuring that researchers can think about translation from day one means expanding institutional capacity and infrastructure.

“We’ll be doing everything we can to further establish Lehigh as a good partner for industry,” says Coulter. “The more streamlined the approach to putting contracts and agreements in place, the more effective we’ll be at technology transfer.”

They’re also proposing a physical research translation hub and prototyping facility. The hub, which Coulter envisions somewhere on the Mountaintop campus, would be a one-stop shop of sorts where researchers, entrepreneurs, mentors, and industry experts can gather for guidance and advice.

“It’s not something we’ll set up right away, but likely in year three or four of the grant,” he says.

As Coulter and his team begin the work of rolling out the mission of ART, it’s important to consider just what an award of this significance says about Lehigh as a research powerhouse. After all, the university was one of just 18 institutions across the country who received an NSF ART grant, and of those, only five received the full $6 million.

“The process was extremely competitive,” says Coulter. “That fact that we were one of the five who got the full amount says that Lehigh was among the best in the country at putting forth a university-wide plan with a truly interdisciplinary team. And that we are committed to doing this well and making a real impact on our society.”