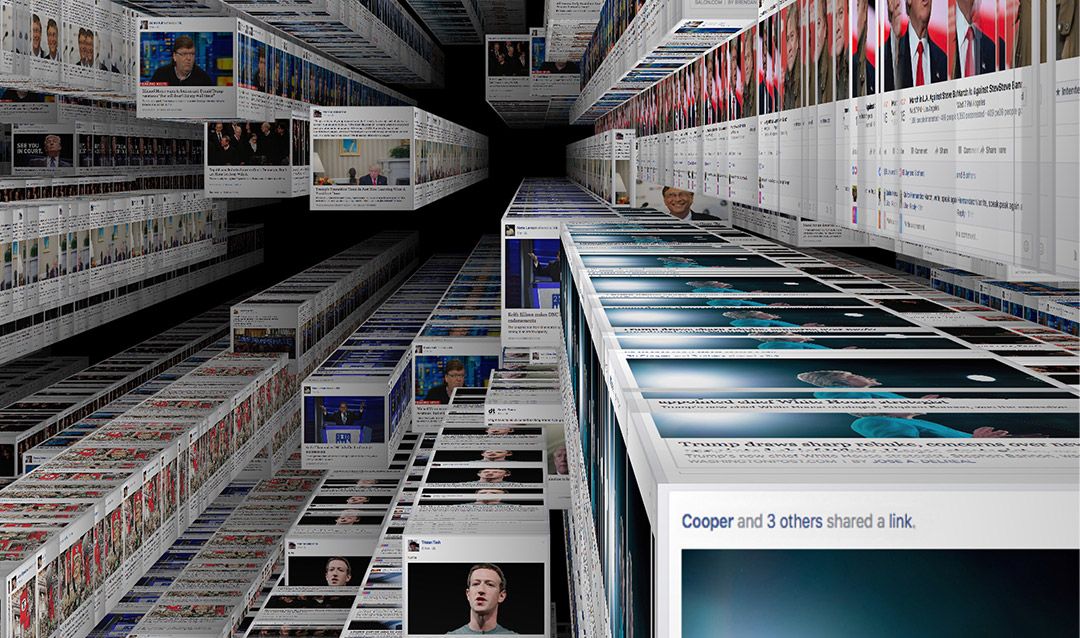

Have you checked your Facebook, Twitter or Instagram account recently? Maybe you’ve used Google Maps to get you to your current destination. Speaking of Google, you’ve probably used a search engine in the last 24 hours. How about shopping at Target?

All of those tasks, somewhere along the way, require an algorithm—a set of rules to be followed in problem-solving operations.

Social media uses algorithms to sort and order posts on users’ timelines, select advertisements and help users find people they may know. Google Maps uses algorithms to find the shortest route between two locations. And Target plugs a customer’s purchases into algorithms to decide which coupons to send them, for instance, deals on baby items if they’ve been purchasing items someone who is expecting a baby might purchase.

The inferences these computer algorithms make using data such as gender, age and political affiliation, among other things, can be frightening, and they raise a plethora of privacy concerns.

Eric Baumer, the Frank Hook Assistant Professor of Computer Science and Engineering, is studying it all, from how people interact with these systems, to how nonprofits can better use algorithms, to the privacy concerns that accompany the technology. He has received a number of National Science Foundation (NSF) grants for his work on human interactions with algorithms, including a National Science Foundation Faculty Early Career Development (CAREER) award for his proposal to develop participatory methods for human-centered design of algorithmic systems.

Baumer’s research into algorithms coincided with an interest in politics, which began when he was a graduate student in the mid-2000s, a time when blogging became popular. Many researchers studied bloggers and analyzed blog content, Baumer says, but he wondered if anyone was reading the blogs. He completed a “qualitative open-ended exploration of people reading blogs.” Through that, he discovered the sub-ecosphere of political blogs.

That led Baumer to complete studies on how people read and engage with political blogs, and then, for his dissertation, he studied computational techniques for attempting to identify conceptual metaphors in written text. Once Baumer started working as a postdoctoral researcher at Cornell University, he says, he became interested in the broader concept of framing political issues. Funded in part by an NSF grant, his work—some of which he has continued at Lehigh—examined computational support for frame reflection.

Baumer refers to the approach he’s taking at Lehigh as human-centered algorithm design. His work specifically centers on getting people whose expertise lies outside of computing involved in the design of algorithmic systems. In addition to the people who are using the systems, Baumer wants to involve in the process the individuals whose data is being analyzed.

Baumer says he already had developed many computational techniques and interactive visualizations heading into the project, but he doesn’t want to assume those are the tools necessary for the job.

“I don’t want to go in looking for nails because I have a hammer,” Baumer says.

For example, he is currently working with a PhD student on conducting interviews at a journalism nonprofit and a legal nonprofit to better understand their existing practices of data analysis. Baumer says the journalism nonprofit’s approach is very tech-savvy, but the legal nonprofit isn’t as well-versed in the technology. Instead, the legal nonprofit is working more on analyzing legislation across different jurisdictions and trying to understand differences and similarities.

“What we’re looking at is trying to figure out what is it that they’re doing right now and what are the design opportunities,” Baumer says. “Rather than going in wielding the computational hammer and saying, ‘We have this tool, wouldn’t it be awesome if you used it?’”

The main goal, says Baumer, is to create relevant and impactful systems that people are going to actually use. He envisions the tools built as a result of his research impacting and influencing the readers of the journalism nonprofit, as well as the legal experts consulting the reports generated by the legal nonprofit.

“In terms of both, the contribution would be: Here are methods that people can use for doing this kind of work, and then here are concrete tools, artifacts and things in the world that have an impact on people’s lives,” Baumer says.

This story originally appeared in the Lehigh Research Review. Read the full story by Stephen Gross.