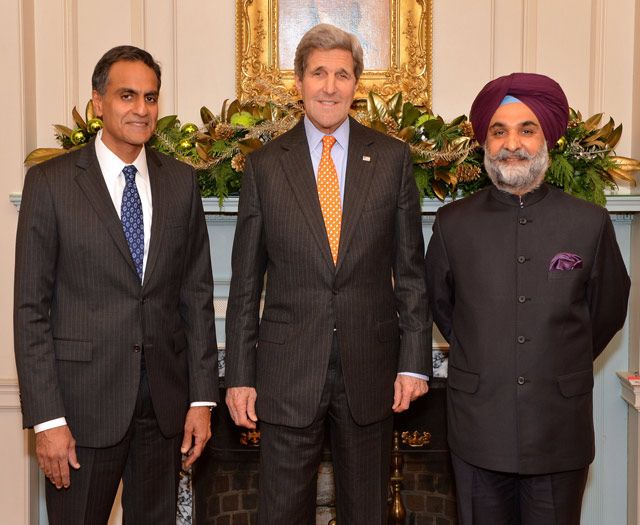

Richard Verma ’90 was appointed U.S. Ambassador to India in 2014 by President Obama and approved unanimously by the U.S. Senate. In two years in India, he has visited 52 towns and cities in 21 states, a level of activity that prompted U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry to say, “we may [be doing] more with India, on a government-to-government basis, than with any other nation.” Verma holds a B.S. in industrial engineering from Lehigh and law degrees from American University and Georgetown. As assistant secretary of state for legislative affairs under Hillary Clinton, he received the Distinguished Service Medal, the State Department’s highest civilian honor.

Q: What attributes are most critical to the diplomatic profession?

A: U.S. diplomats come in all shapes and sizes. Today’s diplomatic corps represents the diversity of Americans in terms of gender, race, sexual orientation, socio-economic background, political-affiliation and geographic origin. In representing the United States, our diplomats proudly embrace this diversity, while also sharing a core set of values and characteristics. This includes curiosity, creativity, and a passion for policy, people and cultural ties; strong analytical, communication and interpersonal skills; developing subject area expertise; and a genuine interest in the region or country of assignment. Flexibility and patience are also key, and my personal favorite is the ability to listen closely to others. If you understand the situation, the perspective and personality of the people you are working with, good decisions and real progress will follow.

Q: How can a modern engineering education contribute to the preparation for a diplomatic career?

A: Engineering and diplomacy both require careful problem solving skills, rooted in facts, science and critical thinking to achieve the best outcome. Like engineering, diplomacy and statecraft require an ability to analyze, interpret and apply information; create and implement solutions; work in multidisciplinary teams; as well as resourcefulness and problem solving; oral and written communication; and attention to detail. Broadly speaking, using all the tools in your toolkit to meet the challenge at hand—whether inventing an innovative design for a water system or developing climate change policy. An education curriculum that develops these qualities in students prepares them well for life in a globalized world, as much as it does for their specific discipline, including diplomacy.

Q: What are the most important of the common values and interests that India and the U.S. share?

A: Much is spoken about the ties between the world’s oldest and the world’s largest democracies, but I think that it is our shared values that bring us together. Both of our constitutions start with the same three words “we the people.” We both respect minority rights and diversity, and we have federal systems, with a multitude of states that can be so different from coast to coast. We are societies bound by the rule of law. We both are working to uphold the post-World War II order across the Asia Pacific and beyond, an order where international law and rules matter. And our people share so much in common—commitments to education, innovation, learning, family and so much more. It’s no surprise that the Prime Minister recently called us “natural allies.”

Q: What role can U.S. academia—faculty members and students—play in helping nations with developing economies? What can these students and faculty learn from India?

A: The U.S. and India have a number of formal education programs that foster exactly this type of dialogue and exchange. For example, check out this program focused on engineering: http://iusstf.org/story/53-49-Research-Internships-In-Science-and-Engine... (RISE). The U.S. Department of State’s Passport to India initiative was set up to encourage more Americans to consider studying in India. Earlier this year it launched an online course entitled “The Importance of India” to help pique American students’ interest in coming to India. The number of Americans studying in India has remained relatively flat at approximately 4,500 (in comparison with 132,000 Indians in the U.S.!)—and we hope that this will increase in the future!

Look into study abroad programs in India, and consider hosting Indian students at Lehigh! Aside from the established cross-cultural programs, I would encourage students to get out of the U.S. and see the world. Get a passport, check out www.travel.state.gov, make arrangements and go. By meeting and understanding people in other places, you will begin to see similarities, universal truths and some local realities. Spend time with the youth and academics in your host country. Understand how their engineering students are different from and similar to you and your peers. Compare and contrast their teachers, teaching styles, libraries, laboratories with what you have. What systems and approaches do they use to address the challenges they face in their personal lives and in the society at large? How do they solve their problems? How are our lives, countries and economies connected? By learning, talking, making personal connections, you can begin to get a feel for the avenues for cooperation, and for collaboration on innovative solutions to shared challenges. That is how you can get going. Just take the first step.

Q: STEAM (science, technology, engineering, the arts and mathematics) education is catching on in America. Is India also encouraging versatility in engineering students?

A: Ever since its independence in 1947, India’s leaders have placed great emphasis on education in general, and STEM education in particular. Note that the emphasis is generally on STEM, not STEAM…but that’s changing too. It is estimated that up to 1.5 million engineering graduates complete their education in India each year. Just like in the U.S., India has a diverse educational system, with some top notch schools that are on par with the best in the world. Over time, the diversity of specializations has broadened in India, and each institution has its own approach to teaching and grooming students, so it would be difficult to generalize.

Q: How can we increase the flow of college and high school students from India to the U.S.?

A: The U.S. has some of the world’s best universities—at all levels and in all fields—and already India is the second highest sender of students to the U.S. after China. Last year, there were a record 132,000 Indian students in the U.S.—two-thirds of them at the graduate level and four-fifths of them in the STEM and business fields.

The U.S. promotes student mobility through EducationUSA—the U.S. Department of State’s official network of advising centers providing accurate, current and comprehensive information about higher education in the U.S. EducationUSA in India has seven centers with more than 30 advisors, and this year we are focused on ensuring that even more Indians make EducationUSA a part of their higher education journey. Of course, affordability can be an issue, but Indian students are generally well aware of the first rate education they can get in the U.S., and the competition can be tough.

Q: While 250 million people in India lack electricity, the achievements of Indian scientists rival those of Westerners. Will these advances help India bypass certain stages in the typical progress from developing to developed nation?

A: Yes. ‘Leap frogging,’ particularly in energy, telecommunications, health and infrastructure will be a big part of India’s development. It is often said that two-thirds of the buildings and infrastructure of India in 2030 have yet to be built. This allows India to incorporate best practices into infrastructure projects that are built from scratch, rather than retrofitting existing buildings (at quite an expense). Everything from energy efficiency, safety codes and using environmentally friendly materials can be part of the process—to an extent city planners in the developed world could only dream of. By 2030, India will be the world’s largest country by population and the third largest economy. The advances that are bound to occur here will be transformational.

Q: What are some facts regarding India’s progress in technology that might surprise American readers?

A: India, a country of nearly 1.3 billion people (i.e., over four times the size of the U.S.) is a land of contrasts, much like our own country. Just like in America, if you were to compare families on the Navajo Nation in rural New Mexico with those in our own urban neighborhood in Pennsylvania, you would find vast differences. The same is true for India. Today’s young Indian innovators are creating new products, services and ideas that offer solutions at a fraction of the cost of traditional technology solutions. Just as an example, the penetration of cell phones in India has been phenomenal, with over a billion users. Not only has the cell phone penetration into the farthest reaches of India allowed people to be connected, the smart phone has enabled a surfeit of services to be rolled out: from banking and financial inclusion to health, education and entertainment, the cell phone has become a literal lifeline. Other advances like India’s indigenously developed railway infrastructure and technology have created physical connectivity among people, along with important industrial connection such as ferrying coal from Jharkhand to Punjab; grains from Punjab to Tamil Nadu; and automobiles from Tamil Nadu to Assam and Kashmir. Thanks to its creative youth, free market economy, strong educational system, and social and economic mobility, we see a lot of potential for yet even more progress, but given India’s size, it will take time. And yes, the innovations brought to the fore certainly have the potential to allow India to skip, in some arenas, certain stages in the traditional model of development.

It also might surprise Americans to learn that India has a very active and advanced space exploration program. India launched its first satellite more than 40 years ago. It also launched a moon orbiter, and in 2014, India became the first country to launch a Mars orbiter which succeeded on the first attempt.

Q: How much progress has India made in building its energy infrastructure?

A: A lot. Until 2014, India, from a national electricity grid perspective, was really five disconnected regions. Today, because of investment in transmission infrastructure, it is now possible to ‘wheel’ electricity generated from a wind turbine in the South up to the North East where it is needed, or vice versa. This drives down prices and adds stability to the national grid such that if there is no wind in one area of the nation, solar generated power can be wheeled in to compensate. A true national grid also allows plants to generate electricity anywhere in the nation and then transmit that power elsewhere.

India has also been forward leaning in energy policy reform such as requiring states to allow transmission of renewables without charge as well as opening up infrastructure development to foreign ownership (FDI), which encourages capital investment. India has the world’s most ambitious renewable targets—175 GW by 2022. We have been strongly supporting those goals, which, if achieved, will revolutionize how power is generated, transmitted and consumed. It will also have a dramatic impact on carbon emissions and our collective battle against climate change.

Q: Please discuss some examples of U.S.-India scientific and technical cooperation.

A: So many to choose from! If I had to name a few, I would say the space program where NASA and the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) have collaborated for decades and helped each other move the science forward; agriculture where U.S. agriculture experts helped India usher in a green revolution, becoming a food-sufficient, food-exporting nation; education — the U.S. was instrumental in the establishment of the Indian Institute of Technology at Kanpur, and our exchange programs, including the Fulbright-Nehru program have, for decades, brought American teachers and students to India and Indians to the U.S.; energy — the Tarapur Nuclear Power Plant that was the product of U.S.-India cooperation in nuclear energy in the early 1960s. It is still operational today and we have now built on that to the next phase of the U.S.-India Civil Nuclear Agreement in which the U.S. will partner with India to help address energy demand using nuclear energy; science — American and Indian scientists in a variety of fields have collaborated with each other and their institutions in important scientific advances. And of course there are the many other people-to-people connections, be it in information and communication technology, physics, chemistry, biochemistry, nanotechnology, agriculture or health sciences. You name it, and we’ve been there, done that, and are building more ties every day. As they say in Hindi about the U.S.-India relationship, “Chalein Saath Saath,” Forward Together We Go.

Interview by Kurt Pfitzer