Zesheng Liu, a second-year PhD student in the Department of Computer Science and Engineering, was awarded Best Paper at the NeurIPS 2024 Workshop on Tackling Climate Change with Machine Learning, among a field of submissions representing some of the tech world’s biggest names.

“I thought for sure that the paper that came from Amazon would win,” says Liu, who is advised by Maryam Rahnemoonfar, an associate professor of computer science and engineering and civil and environmental engineering. “So when I heard I’d won, it was hard to believe at first.”

Liu was awarded the distinction for his paper that focuses on developing a machine learning method to better predict the thickness of ice sheet layers.

Climate change has accelerated ice sheet melting in both Greenland and Antarctica, and such melting can influence sea level rise, which increases the risk of flooding in coastal communities. Current estimates, however, for just how much the ocean might rise range from 26 to 98 centimeters by the end of this century. Such a broad range is partially attributable to an incomplete understanding of just how thick the ice actually is; if researchers could more precisely measure that thickness, they could refine estimates of sea level rise, which will better help communities prepare.

Measuring the layers within the ice sheet is challenging. The topography of the ice bed, snow accumulation, and the dynamics of the ice itself make it difficult to obtain accurate measurements. Gathering ice cores is the traditional measuring technique, but it’s expensive, laborious, limited in depth and scope, and invasive to the environment.

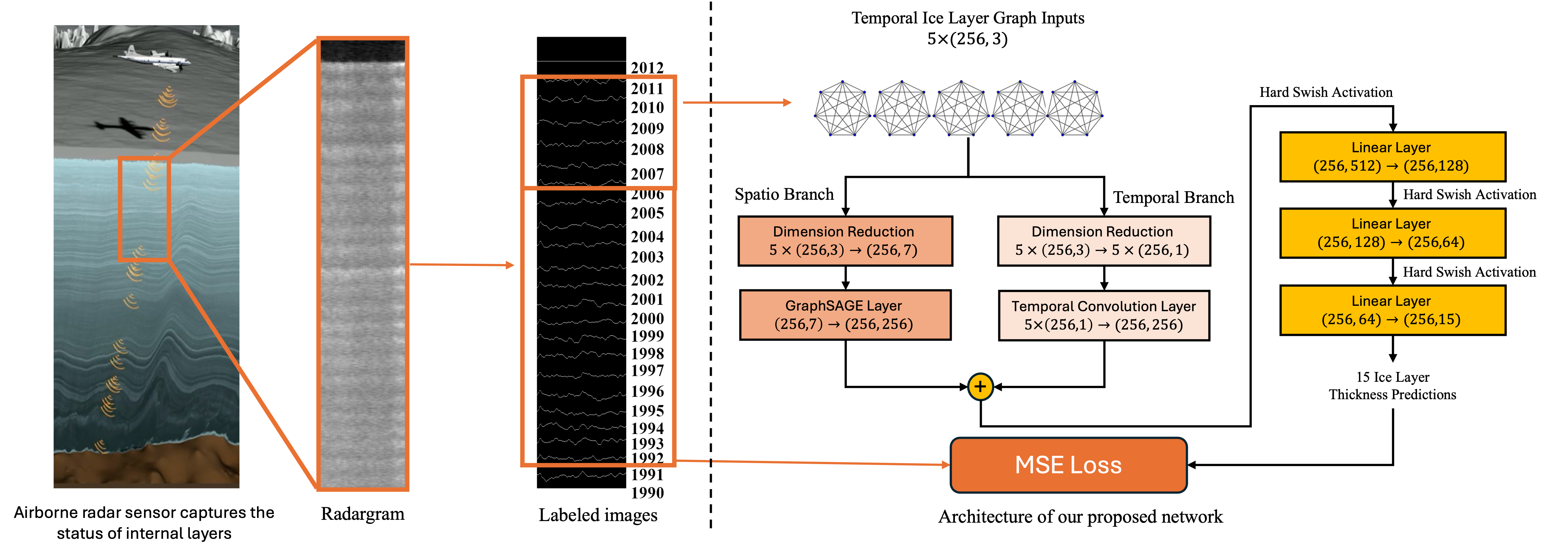

A more popular method is airborne radar, which can penetrate the ice and use the reflected signals to measure thickness. But the data gathered by radar sensors is not as clean as natural images, making individual layers—especially those deep within the ice bed—indistinguishable.

“It's difficult to track those deep ice layers,” says Liu. “They have been there for a very long time, and have undergone a lot of physical changes, like melting, which can blur the boundaries between the layers. So no matter what method you use to measure ice thickness, it’s very hard to make accurate predictions.”

Zesheng and his advisor have developed an experimental machine learning model called a multi-branch, spatio-temporal graph neural network that could work in tandem with information generated by the radar sensors.

“There’s a huge amount of data that’s collected by the radar, so we’ve created a model that can more efficiently process it,” he says. “In addition, we’re using the radar data generated from the first five layers of ice, which is less noisy and more accurate than results from deeper layers, and we’re using that to predict the thickness of deeper layers.”

Ultimately, Liu says he hopes their model—which they are continuing to refine in both scope and efficiency—will be used by climate researchers to make more accurate predictions of ice dynamics and sea level change.

In the meantime, winning Best Paper for his first research project as a graduate student has motivated Liu to work even harder.

“Climate change is causing huge problems around the world,” he says. “I hope that my research might someday form the backbone of climate models that better help us prepare for the changes to come.”