|

As a 2021 recipient of the NSF CAREER award, Srinivas Rangarajan joins a distinguished group of Lehigh faculty recognized nationally for early-career excellence. Read more in the next issue of Resolve. |

Chalk up 2020 as the year data visualizations truly went viral.

Across the internet and social media, simulations with bouncing balls helped us understand the spread of disease, and interactive charts and graphs gave us a better grasp of how masks, lockdowns, and social distancing might flatten the COVID-19 curve.

“People have been exposed to the world of mathematical modeling through this pandemic,” says Srinivas Rangarajan, an assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering (ChBE). “Models and their resulting projections have been the cornerstone of a lot of the recent decision-making in the United States in response to coronavirus.”

Rangarajan shared his expertise in computations by mentoring students in a recent Mountaintop Summer Experience Project that created visualization modules for STEM-based learning—including one with an epidemiological focus.

“You can manipulate the parameters to build any sort of disease-spreading event and then get a sense of the dynamics, or how the different populations—exposed, hospitalized, recovered, and so on—change over time,” he says. “I see it as a chemical engineering problem or, at the very least, one that uses similar mathematical modeling concepts and engineering processes.”

Rangarajan considers himself an “accidental” chemical engineer, having been set on the path following his high school exams in India. However, he quickly found that the discipline’s combination of chemistry, physics, and math suited him. His decision to take a computational direction was, in part, driven by practicality (“you don’t need a lab space or infrastructure, just a laptop”) and solidified by experiences.

“My internship was about building mathematical models and chemical processes for making polymers,” he recalls. Later on, he went to the Netherlands to work for Shell, developing models for a new chemical process for converting natural gas into fuels and lubricants. “These opportunities gave me insight into the value of computational sciences and just how useful modeling can be, not just in terms of understanding, but also for process optimization and maximizing profitability.”

A desire to delve into academic research took him first to the University of Minnesota to work on modeling complex reaction networks in biomass and hydrocarbon conversion, a project that Dow partially supported. As a postdoc at the University of Wisconsin, one of his projects was with BP on removing sulfur from crude oil to produce ultra-low sulfur diesel. The experience trained his sights on heterogeneous catalysis, while introducing him to quantum chemistry.

“With quantum chemistry, you can computationally understand what’s happening in a reaction system at the level of individual atoms and then use that information to design a new chemical process.”

“With quantum chemistry, you can computationally understand what’s happening in a reaction system at the level of individual atoms and then use that information to design a new chemical process.”

Answering increasingly complex research questions requires interdisciplinary collaboration, says Rangarajan, who points out that he always had a pair of advisors (one who specialized in mathematics; the other, chemistry or catalysis) throughout his advanced studies.

“Modern science and engineering isn’t done in an individual setting. You can’t solve today’s problems by only doing computations or only experiments. You need to team up and use a combination of tools.”

That mindset—combined with an appreciation for Lehigh’s strengths in experimental catalysis, synthesis, materials science, and microscopy—brought him to the Rossin College in 2017, a decision that has resulted in collaborations with fellow ChBE faculty members Jonas Baltrusaitis, Mark Snyder, Jeetain Mittal, and Israel Wachs, among others.

On the topic of catalysis, Rangarajan is working with Baltrusaitis to find energy-efficient alternative routes to produce ethylene and propylene (used in plastics). The current process consumes more than three exajoules of energy and releases more than 200 metric tons of carbon dioxide globally every year.

“We are moving away from using conventional sources of carbon such as crude oil to newer sources such as biomass, shale gas, and even waste CO2 to produce various products,” he says, “so the question that interests me is how do we engineer new catalytic processes to make them more material efficient and have less CO2 impact?”

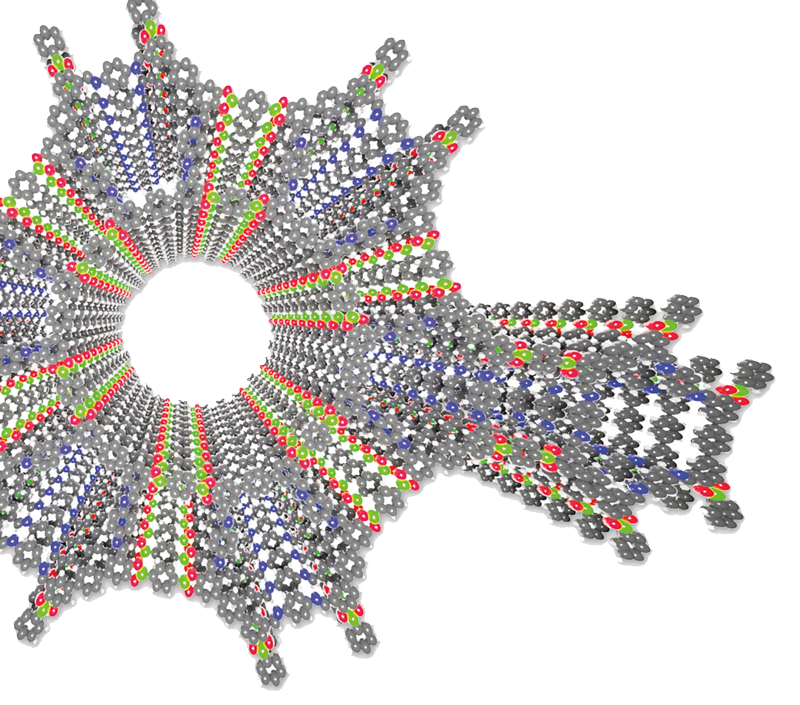

Rangarajan was also awarded a $420,000 NSF grant with Snyder (a materials synthesist) and Mittal (an expert in molecular simulation) focused on an emerging class of porous materials called covalent organic frameworks (COFs). The team is developing a computational method to guide experimental efforts in synthesizing COFs, which have tiny (i.e., sub-nanometer scale) pores, from billions, or possibly trillions, of building-block combinations.

“Because we can make these materials with pores of multiple sizes and structures, they can find a wide variety of applications in areas like catalysis, energy storage, and drug delivery,” Rangarajan explains.

The group’s workflow, which integrates computational and experimental approaches, illustrates the power of tackling a problem from multiple angles. To be successful, he says, requires “a critical group of people who provide a complementary perspective to your own.”

ILLUSTRATION CREDIT: Courtesy of Christopher Rzepa