Run or jump, and the impact of your feet striking the ground reverberates up through your bones, muscles and spine, and even to the cells in your bones.

In biomechanical terms, you have imposed dynamic loading on your body parts. if you overdo it, like a soldier in basic training, you risk injury. if you underdo it, like a bedridden person, you weaken your ability to absorb shock.

And as you age, like the chassis of a car, your body frame needs better shock absorbers, regular maintenance and, sometimes, a replacement part or two.

Akady Voloshin, professor of mechanical engineering and mechanics, has spent more than two decades studying the effects of dynamic loading on the musculoskeletal system.

Working with researchers at Università degli Studi della Basilicata in Potenza, Italy, he is subjecting a segment of a pig’s spine to compression, extension and lateral bending, in an effort to learn how to measure disc displacements under various loads.

“This study holds promise for investigating the behavior of tissue,” says Voloshin, “which could lead to a better understanding of spine and disc injuries in humans and, ultimately, to improved surgical treatment of degenerative disorders of the spine.”

Working with researchers in Lehigh’s Sherman Fairchild Center for Solid State Studies, Bioengineering program and electrical and computer engineering department, Voloshin is studying osteoporosis.

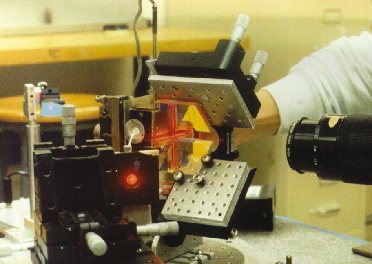

The group wants to know why bones lose their ability to respond to dynamic mechanical stimulus. The lack of response slows osteogenesis, the process of laying down new bone material. Voloshin, seeking to identify the mechanism responsible for osteoporosis, has used a polymer-based mEmS device to observe living cells and measure their mechanical properties.

Working with Israel’s loewenstein Rehabilitation hospital, Voloshin studies runners to measure fatigue’s effect on the ability of the musculoskeletal system to dissipate heel-strike shock waves on the tibial tuberosity and sacrum.