She had to take a second after reading the email.

It was May 2020 when Veronica Meyer ’22 saw the message from chemical and biomolecular engineering (ChBE) professor James Gilchrist.

“He wanted to know if there were any students interested in doing something over the summer if their internship had fallen through due to COVID-19,” says Meyer. “He was basically asking us, how can we improve the ChBE program? As a student, you don’t usually get asked that.”

Soliciting that level of feedback was new for Gilchrist, too. But after the pandemic derailed so many internships, Lehigh instituted a virtual research opportunity for undergrads—and it got him thinking. His work on the fundamentals of particulate systems was too experimental for Zoom, but he didn’t want to miss out on tapping students for their expertise. “They have so much to offer,” he says.

The result was a focus group of students like Meyer who got a chance to do something they never imagined having the opportunity to do: conceive and design a new class for their peers. “Coffee and Cosmetics: Engineering of Consumer Products” is open to all Lehigh students and introduces the concepts of chemical engineering in relevant, relatable ways. It debuted virtually in Spring 2021 and is being held in person this fall.

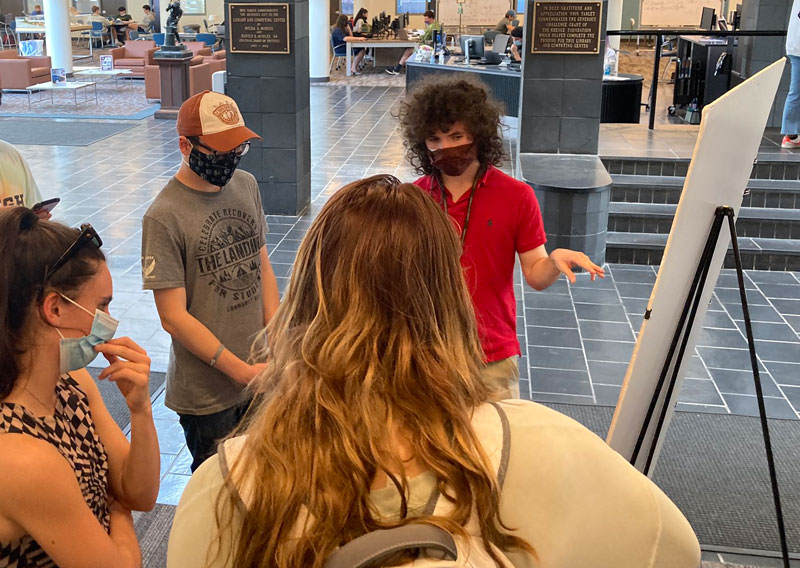

|

Students from LU Coffee and Cosmetics class present their midterm projects in October outside The Grind coffee shop in Fairchild Martin Lab. (Photo courtesy of @LUCoffeeandCos1) |

Taking a fresh look

It’s safe to say that chemical engineering has an image problem.

“When I tell people my major, their first reaction is, ‘Are you sure you want to do that? How do you have a life?’” says Megan Walker ’22, who, along with Meyer, helped develop the course and served as a teaching assistant this past spring.

Part of the problem, says Gilchrist, is that the focus hasn’t been on making the material fresh and pertinent to students. On day one, he says, they’re shown a distillation column (a vessel used to separate liquids) and process equipment, and it’s just expected that they’ll memorize the equations and (eventually) grasp the concepts. “But as a consumer, you don’t interact with those things,” he says. “Historically, not much thought has gone into how to relate these ideas to things students actually use, like refrigerators and coffee makers.”

Gilchrist had already started addressing this relevance problem with the introductory chemical engineering course, which he co-teaches with associate professor Angela Brown. So it was top of mind after he assembled the student focus group last summer. As a team, they came up with several ways to improve the program. They started mapping out activities they could do with local schools and how to build a stronger social media presence. When Gilchrist mentioned a coffee course a colleague had started at the University of California, Davis—one that eventually grew into a research and teaching facility—the group loved the idea of creating a similar class. But they wanted theirs to have a broader scope.

“Of the 10 students, seven were women,” says Gilchrist, “and they said, ‘You must have cosmetics in here, it’s such an easy way to connect with, well, everyone.” Sure, the industry is more heavily marketed toward women, but products like deodorant, lotion, toothpaste, and shampoo are universal. “They came up with the idea of developing a syllabus and pitching it to the department as a new class.”

The students split the course into separate sections on coffee and cosmetics, ending each with a project. They designed the class structure and the instruction sheets, homework, quizzes, and final projects. They came up with the grading criteria, too. They wanted the class to be accessible to all students, so all math, physics, and chemistry was high school level, and there were zero requirements to memorize and spit back equations on tests.

The group focused on developing modules and hands-on labs that would engage students’ creativity. They also wanted to give them ownership over what they learned. To that end, they came up with using Google Jamboard, an interactive whiteboard, to kick off each section. The tool would allow students to identify and rank what it was about coffee (roasting, harvesting, extraction, environmental impacts, for example) that piqued their interest, and the lectures would be tailored to those topics. Final projects would be open-ended. They could do a case study or create a new product utilizing the principals they’d learned throughout the course.

“In engineering, you usually have a pretty tight curriculum,” says Gilchrist. “We don’t stop to ask, ‘So what do you think about what you’re learning?’ I was floored by all the creative ideas they had about how we could teach better.”

Stirring up discussions

Stirring up discussions

When the students presented their syllabus to the ChBE faculty at the end of last year, “it was definitely nerve-racking,” says Meyer. “I was a junior, so they were my professors.”

But their pitch, done over Zoom, was a hit.

“They did a great job of explaining the benefits and why we should do this,” says Brown. “At that point, the program didn’t offer any classes to nonmajors.” She says that people often don’t know what chemical engineers do—“I didn’t know when I chose this as a major,” she admits—so the class gives students a chance to experience the discipline and see if it resonates.

The first Coffee and Cosmetics cohort included students majoring in finance, business, and chemical engineering, and since it was on Zoom, some high school students as well. TAs like Meyer and Walker were in constant touch with their student groups, guiding them through the class and asking for feedback.

And that feedback? It was overwhelmingly positive.

“The students really liked how the class was focused more on applications as opposed to memorizing calculations and taking exams,” says Walker.

They also liked how accessible it was: “It was taught at a level that wasn’t exclusive,” says Meyer. “It was comprehensible to everyone, and they were excited to be learning about something they use every day.”

It wasn’t just the students who were learning. Because the focus group had designed the course, and because students in the class were following their own interests within the topics of coffee and cosmetics, Gilchrist found himself in an unusual position.

He says he “learned a ton,” especially from the business majors as they presented ideas around the design and marketing of new products like tea bags for coffee, or coffee-infused wine, or cosmetics blended to a customer’s specifications.

Their discussions about products often went beyond chemistry and biology to culture and diversity. For example, how the marketing of cosmetics is often centered around those with relatively pale skin. Or how socioeconomic factors can have a real impact on how students interpret some of those foundational engineering concepts, like the Bernoulli equation (the relationship between flow rate and pressure).

“I can lecture for two hours on something like that, but if I were to instead start by asking the students, ‘Can you give me examples of where you see fluids moving very slowly or very fast?’ there could be some culturally rich answers to a question like that,” he says. “What I’ve learned most is to ask the students what they know, before I tell them what I know.”

Coffee and Cosmetics is now underway in person, and Gilchrist hopes to add a competitive aspect (another of the focus group’s ideas) that will have students vying for who can brew the best coffee and make the best lip balm.

For him, the genesis of the class and its rollout has been an inspiring, humbling, and eye-opening experience. And it’s changed his perspective on what it means to engage his students, and by default, what it may take to attract more of them to this unique, varied—and yes, tough—discipline.

Listen In

Listen In