By Christine Fennessy

The future of research is bright. Quite literally.

The future of research is bright. Quite literally.

That fact is clear to anyone who walks through Lehigh’s new Health, Science and Technology Building. With its open floor plan dotted with islands of live plants and ringed by giant windows illuminating all its laboratory and public spaces, it’s the university’s boldest statement yet of its commitment to investing in both cutting-edge research and human potential.

“The HST Building is unlike any other building on campus, and its difference reflects what we believe the future of research will look like,” says Steven McIntosh (pictured), professor and chair of the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering. “And by that I mean, it’s a building that is designed from the start to encourage people to interact.”

For instance, the main stairwells aren’t continuous. So getting from the basement to the second floor, for example, requires taking one set of stairs, and walking the length of the next floor to the second set of stairs, a design feature meant to encourage interaction among faculty, staff, and students.

The labs that line nearly the entire length of the first and second floors seamlessly flow from one space to the next without division by walls or doors. The glass-lined conference rooms allow users to see out and passersby to view what’s happening inside.

With the exception of the suite occupied by the College of Health, all the faculty offices are clustered—without regard to departmental affiliation—in the center of the building, within steps of the labs and graduate students. The graduate students themselves are seated amongst their peers from other programs and departments, and work in cubicles surrounded by greenery, cast in natural light, and enticingly placed around cozy common areas.

“We’ve removed all boundaries within the building,” says McIntosh, who served on the facility’s design committee. “So if I open my office door, I immediately walk into a common student area, and there are people eating lunch, or having coffee, or talking about their research. This barrier-free space reflects the idea that research now is both interdisciplinary and highly collaborative.”

“We’ve removed all boundaries within the building,” says McIntosh, who served on the facility’s design committee. “So if I open my office door, I immediately walk into a common student area, and there are people eating lunch, or having coffee, or talking about their research. This barrier-free space reflects the idea that research now is both interdisciplinary and highly collaborative.”

Lehigh has long embraced the interdisciplinary approach to research. Now, with the purpose-built design of HST, there is a physical manifestation of that “better together” ethos, and the implications of it could be significant, says Elsa Reichmanis (pictured), professor and Carl Robert Anderson Chair in Chemical Engineering.

“The facility demonstrates Lehigh’s interest in promoting collaboration and opening new areas of research and investigations that could have real impact, not only on the immediate area and on Pennsylvania, but nationally and globally as well,” she says.

Building ‘research neighborhoods’

Building ‘research neighborhoods’

While the university is known for its exceptional research and cutting-edge facilities, HST will enhance ongoing investigations by combining access to equipment with human capital.

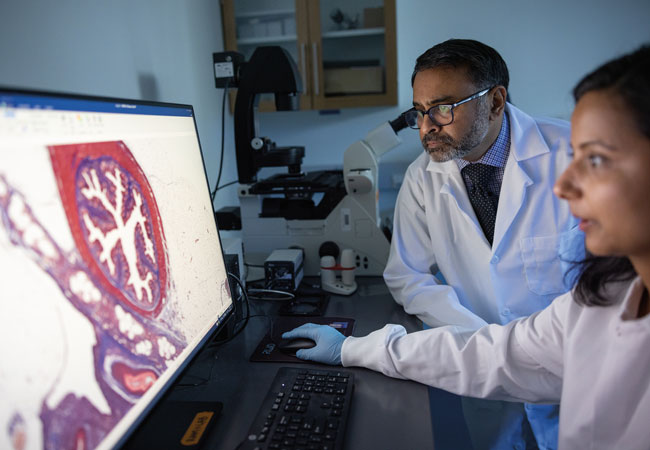

“There are so many resources and facilities spread across our campuses,” says Anand Ramamurthi (pictured), professor and chair of the Department of Bioengineering. “In the past, it’s been difficult trying to consolidate them and provide them sufficient visibility so that faculty and students are aware these resources exist. Because HST is meant to create a community of researchers who work together, it has brought all these resources, facilities, and equipment under one roof.”

Ramamurthi’s research team creates nanotherapeutics for vascular tissue repair, and also develops stem-cell-inspired approaches for the treatment of proteolytic diseases—disorders like aortic aneurysms and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) that are characterized by the breakdown of proteins. Within HST, he’ll have access to the complete research infrastructure he needs for his own investigations as well as facilities like a data visualization lab (see “Next-gen tech enables next-level collaboration in materials research”) and high-speed computational resources that will enable him to expand his research footprint.

And while individual research teams have their own designated lab space, the open concept of the laboratories gives all researchers immediate access to those with expertise outside their own.

“Students and investigators can walk through each other’s labs,” he says. “You can see what others are doing, what equipment they have, and vice versa. By putting me and my team in a space adjacent to people outside our research area, who knows what will come out of it?”

For example, he says, he and his team are interested in using machine learning techniques to predict adverse blood vessel rupture outcomes. “While we are novices in these techniques,” he says, “within HST, we’ll be near the people who are experts in these areas, and that will allow me to identify who I might talk to next, and who I might collaborate with to move my research forward.”

Though he’s been in the building only since January, Ramamurthi says he’s already fielded numerous requests from students and faculty interested in getting trained on his own research equipment.

“And guess what? That opens up new opportunities to talk, because now I can say to them, ‘Hey, you have this microscope. We’d like to try something new. Can you work with us on this?’ So it goes both ways,” he says.

New additions to the Rossin College faculty, including bioengineering professors Tomas Gonzalez-Fernandez (who works on novel cell-instructive 3D printable biomaterials) and Niels Holten-Andersen (who is also on the materials science and engineering faculty and studies bio-inspired synthetic materials with applications in energy, the environment, and health) have also set up their labs in the facility.

New additions to the Rossin College faculty, including bioengineering professors Tomas Gonzalez-Fernandez (who works on novel cell-instructive 3D printable biomaterials) and Niels Holten-Andersen (who is also on the materials science and engineering faculty and studies bio-inspired synthetic materials with applications in energy, the environment, and health) have also set up their labs in the facility.

Also in residence are the first of a growing contingent of faculty with joint appointments in both the College of Health and the Rossin College: data and computer scientist Bilal Khan, who directs Lehigh’s Population Health Data Warehouse, and Gabrielle String, an environmental health researcher who studies water sanitation and drinking-water program implementations and technologies.

While not every piece of equipment within HST will be shared, much of it will be, says McIntosh. Already, big items such as the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy instrument and the low-energy ion scattering instrument have been set up in the building’s basement.

“The idea is that the student makes a sample in the lab upstairs,” he says, “then they can go downstairs and, in a single day, do numerous measurements on this sample—and so it’s all done in one spot.”

McIntosh says that one of the driving principles of the building’s design and location and the selection of its occupants sprung from the concept of creating “research neighborhoods” guided by two research themes, materials for energy and biohealth. Researchers in those areas—from the departments of bioengineering and chemical and biomolecular engineering—were moved from the Mountaintop campus to the neighborhood comprising HST, Whitaker Laboratory, Sinclair Laboratory, and the Seeley G. Mudd Building.

“Now we have materials-, bio-, and health-related faculty in HST right next to Whitaker, which has most of the materials researchers, which is right next to Sinclair with its clean rooms, which is right next to Mudd with its chemistry facilities,” says McIntosh. “So we have this neighborhood of people who might not do the same research, but speak a similar language, and provide complementary expertise, to benefit the whole group.”

Those research thrusts are also present in all HST’s lab spaces, he says. “The themes exist vertically in the building and cross-pollinate horizontally across the floors.”

Seeing the bigger picture

Seeing the bigger picture

The building’s layout and concentration of expertise may perhaps most benefit graduate students.

“My office is basically 10 steps from one lab, 20 steps from another, and 15 steps from where my students are sitting,” says bioengineering and chemical and biomolecular engineering professor Anand Jagota (pictured), who was recently named Lehigh’s vice provost for research. The arrangement creates new opportunities for interaction, he says, and those interactions “are much more natural.”

Jagota, the bioengineering department’s founding chair and the associate dean of research in Lehigh’s College of Health, leads a variety of projects including virus adhesion to cells, how virus-laden droplets get resuspended from surfaces, and improving wound adhesives. While his team has always had access to the equipment they need, Jagota says the spatial organization within the HST Building will allow for greater interaction and collaboration, particularly among graduate students.

“For example, if a student wants to do something but doesn’t know the technique for it, the open, shared lab allows them to reach out to students and faculty from other research groups for help,” he says. “They no longer have to default to asking their advisor. And this enables them to build important relationships that can benefit their own research.”

Building those relationships and exploring new opportunities is key to preparing Lehigh students for the working world, says Reichmanis, whose research includes designing advanced materials for energy storage applications and controlling the organization of polymers for electronic transport.

Building those relationships and exploring new opportunities is key to preparing Lehigh students for the working world, says Reichmanis, whose research includes designing advanced materials for energy storage applications and controlling the organization of polymers for electronic transport.

“I think HST gives students an opportunity to more easily build their networks, because the layout makes it easier to talk with faculty and other students,” she says. “Students will be more engaged, they’ll learn more, and I think the environment here will also help them develop leadership skills in terms of how they start or get involved in new projects and feel empowered to explore new areas.”

McIntosh sees that sense of empowerment developing already. One of his grad students had a recent random encounter in HST with new bioengineering and materials science faculty member Holten-Andersen. The ensuing conversation spawned an idea for that student’s research.

“I think HST changes their sense of belonging and community and being part of the bigger research picture,” he says. “The great hope is that your graduate student comes to you and says, ‘I was talking to this person from this lab and we tried this new experiment,’ and it’s something that you as an advisor hadn’t even considered. We want students to really own things, because in the real world, they’re going to be expected to find the people they need to work with to solve problems.”

Creating community across disciplines

That sense of belonging is real for Simran Dayal, a PhD student in bioengineering. Dayal is advised by Ramamurthi and researches minimally invasive treatments for abdominal aortic aneurysm, a condition in which the aorta, the main blood vessel that delivers blood to the body, enlarges over time. As it grows, it can cause painful symptoms and potentially become life threatening.

“It’s a common disease, especially in older male patients,” says Dayal. “The available treatment options are limited to surgery, which is very risky. So we’re looking at drug delivery nanotherapeutics that we can inject and prevent growth of the aneurysm.”

“It’s a common disease, especially in older male patients,” says Dayal. “The available treatment options are limited to surgery, which is very risky. So we’re looking at drug delivery nanotherapeutics that we can inject and prevent growth of the aneurysm.”

As a fourth-year student, Dayal is used to the more traditional layout, where halls, walls, and doors separate research teams. It made it hard for someone like her—“a bit of a shy person”—to meet her peers and learn who did what.

“The labs in HST aren’t separated by walls, so if I’m walking around and I see someone, I can just start talking to them,” she says. “I’ve gotten to know a lot more people.”

Since moving to the building in January, she’s helped train students on her lab’s equipment, and shared microscopes, plate readers, and freeze-drying systems.

“It’s a very collaborative environment,” she says. “And with HST investing in bigger pieces of equipment, like a 3D bioprinter, it’s exciting to know I’ll be so close to machines like that, as well as to the people who know how to use them.”

John Sakizadeh ’22 PhD also points to the open-concept design of HST as a major factor in enhancing communication between grad students. Sakizadeh, who was advised by McIntosh and graduated in the spring, researched how to synthesize functional nanocrystals for use in converting solar energy into chemical energy.

“It’s interesting being next to a group in the lab that we don’t normally interact with,” he says. “It definitely changes your everyday level of collaboration. If someone needs a chemical, or a fitting for a valve, or training on an instrument, it’s so easy to ask for it.”

For Zeyuan Sun, being embedded in the “research neighborhood” will have a direct impact on his work. A third-year PhD student in chemical engineering who is advised by Reichmanis, Sun studies the characteristics and properties of conjugated polymer semiconductors in organic transistor applications.

For Zeyuan Sun, being embedded in the “research neighborhood” will have a direct impact on his work. A third-year PhD student in chemical engineering who is advised by Reichmanis, Sun studies the characteristics and properties of conjugated polymer semiconductors in organic transistor applications.

“This is a very multidisciplinary field,” he says. “It includes optics, electronics, and solid-state physics, so it requires me to utilize many different resources. HST is right in the middle of all those resources, and that makes it a lot easier.”

He definitely appreciates the beauty of the building, all the natural light filtering through giant floor-to-ceiling windows, the abundance of über comfortable common areas to eat, chat, and rest, and the literal transparency of the lab space. But the thing he likes best? His desk.

“It’s located between my PI’s office and the lab,” he says. “So it’s easy to initiate conversations with her, and whenever I have an idea for an experiment, I can walk into the lab and conduct it immediately. So yeah, that’s my favorite spot.”

Photos courtesy of Douglas Benedict/Academic Image & Ryan Hulvat/Meris