A Lehigh team has successfully predicted abnormal grain growth in simulated polycrystalline materials for the first time—a development that could lead to the creation of stronger, more reliable materials for high-stress environments, such as combustion engines. A paper describing their novel machine learning method was published in npj Computational Materials.

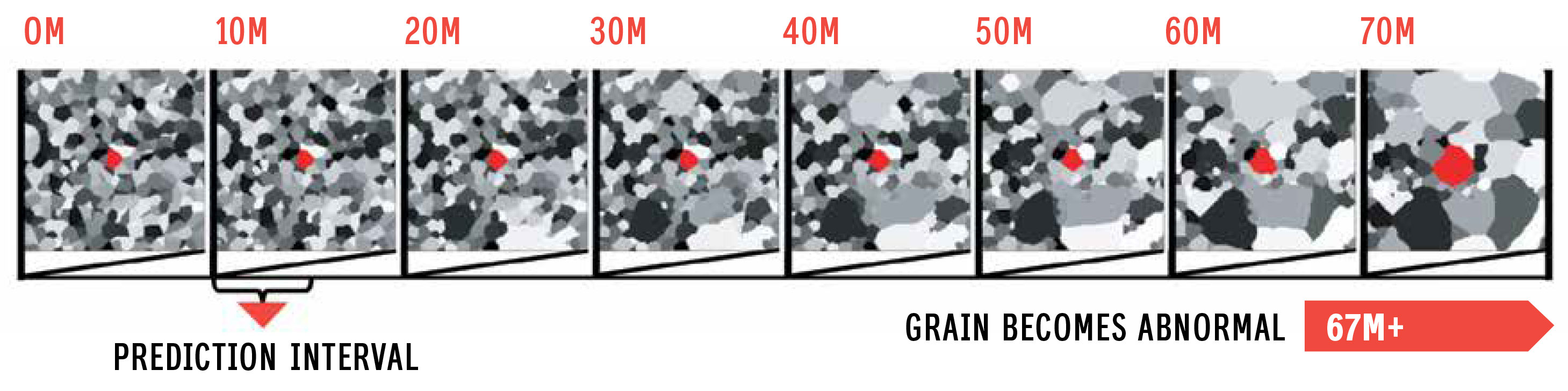

“Using simulations, we were not only able to predict abnormal grain growth, but we were able to predict it far in advance of when that growth happens,” says Brian Y. Chen, an associate professor of computer science and engineering and a co-author of the study. “In 86 percent of the cases we observed, we were able to predict within the first 20 percent of the lifetime of that material whether a particular grain will become abnormal or not.”

When metals and ceramics are exposed to continuous heat—like the temperatures generated by rocket or airplane engines, for example—they can fail. Such materials are made of crystals, or grains, and when they are heated, atoms can move, causing the crystals to grow or shrink. When a few grains grow abnormally large relative to their neighbors, the resulting change can alter the material’s properties. A material that previously had some flexibility, for instance, may become brittle.

When metals and ceramics are exposed to continuous heat—like the temperatures generated by rocket or airplane engines, for example—they can fail. Such materials are made of crystals, or grains, and when they are heated, atoms can move, causing the crystals to grow or shrink. When a few grains grow abnormally large relative to their neighbors, the resulting change can alter the material’s properties. A material that previously had some flexibility, for instance, may become brittle.

“We’d like to be able to design materials intentionally to avoid abnormal grain growth,” says Chen.

Finding stability

Predicting abnormal grain growth has been a needle-in-a-haystack problem. There are countless combinations and concentrations that can go into the creation of any given alloy. Each of those metals must then be tested, which is expensive, time-consuming, and often impractical. The simulation developed by Chen’s team helps narrow down possibilities by quickly eliminating materials that are likely to develop abnormal grain growth.

“Our results are important because if you want to look at that big haystack of different materials, you don’t want to have to simulate each one for too long before you know whether or not abnormal grain growth is going to occur,” he says.

The challenge is that abnormal grain growth is a rare event and, early on, the grains that will become abnormal look just like the others.

Unlocking hidden patterns

To address this, the team developed a deep learning model that combined two techniques to analyze how grains evolve over time and interact: A long short-term memory network modeled how the properties—or features—of the material would be evaluated, and a graph-based convolutional network established relationships between the data that could then be used for prediction.

Initially, the researchers simply hoped to make successful predictions. They didn’t anticipate being able to make predictions so early.

“We thought that the data might be too noisy,” he says. “Maybe the properties we were looking at wouldn’t reveal very much about distant future abnormalities, or maybe the abnormality would only reveal itself just as it was about to happen, when it might be obvious even to the human eye. But we were surprised that we were able to make predictions so far in advance.”

By studying how grains evolved long before abnormalities appeared, the team identified consistent trends useful for early prediction. In this project, Chen and his team conducted simulations of realistic materials.

The next phase is to apply the approach to images of real materials and see if they can still accurately predict the future. The long-term goal, says Chen, is to identify materials that are highly stable and can maintain their physical properties under a wide range of high-temperature, high-stress conditions. Such materials could allow engines to run at higher temperatures for longer before failure.

The next phase is to apply the approach to images of real materials and see if they can still accurately predict the future. The long-term goal, says Chen, is to identify materials that are highly stable and can maintain their physical properties under a wide range of high-temperature, high-stress conditions. Such materials could allow engines to run at higher temperatures for longer before failure.

The team also sees the potential of their novel machine learning method to predict other rare events, thanks to its ability to identify warning signs in complex systems. For example, it might help predict mutations leading to dangerous pathogens or sudden shifts in atmospheric conditions.

“This work opens up an exciting new possibility for material scientists to ‘look into the future’ to predict the evolution of material structures in ways that were never possible before,” says Martin Harmer, Lehigh’s Alcoa Foundation Professor Emeritus of Materials Science and Engineering and a co-author of the paper. “It will have a major impact in designing reliable materials for defense, aerospace, and commercial applications.”

Research Team and Funding

Computer science and engineering PhD student Houliang Zhou and MS student Benjamin Zalatan co-authored the paper (npj Comput Mater 11, 82 (2025)) along with Chen, Harmer, and Joan Stanescu, visiting scholar in Lehigh’s Nano | Human Interfaces (NHI) Presidential Initiative; Jeffrey M. Rickman, Class of ’61 Professor of Materials Science and Engineering; Lifang He, an associate professor of computer science and engineering; and Lehigh alum Christopher J. Marvel ’12 ’16 PhD, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at Louisiana State University.

This work was supported in part by the National Science Foundation, the Army Research Office, the Army Research Laboratory Lightweight High Entropy Alloy Design (LHEAD) Project, and the Lehigh University Presidential NHI Initiative.

Related Links:

- npj Computational Materials: "Learning to predict rare events: the case of abnormal grain growth"

- Rossin College Faculty Profile: Brian Y. Chen

- Lehigh NHI Presidential Initiative: Martin Harmer

- Lehigh NHI Presidential Initiative: Joan Stanescu

- Rossin College Faculty Profile: Jeffrey M. Rickman

- Rossin College Faculty Profile: Lifang He

- Louisiana State University: Christopher Marvel