This fall, a select group of students are learning how to design and build a machine—in just seven weeks.

They’re participants in a pilot course that will serve as the core of the First-Year Rossin Experience (FYRE), an innovative program that re-envisions the way incoming students first engage with engineering.

In lieu of traditional courses and grades, FYRE will empower students to pursue their passions and assemble a digital portfolio of their accomplishments. They will learn how to conduct research and explore real-world problems through six collaborative, project-based learning modules focused on interdisciplinary challenges (such as building a functional machine and a working battery) that connect engineering with subjects like physics, chemistry, and calculus. They will master core engineering competencies through independent learning and mentorship. And they will engage in a yearlong, co-curricular experience—for example, joining a research lab or one of the college’s competition teams, or taking part in a Creative Inquiry project—that will expose them to the range of perspectives and opportunities across the university.

It’s a transformative, radical rethinking of how engineering is taught. It’s also a huge undertaking

“When FYRE is fully implemented, by the 2028 academic year, all first-year engineering students will go through it,” says Derick Brown, a professor of civil and environmental engineering and associate dean of undergraduate education in the Rossin College. “This pilot phase will help us determine the best way to design these modules. Our inaugural cohort of 34 students will complete two modules this fall, with another 70 students completing two more in the spring, in addition to their regular course load, providing invaluable feedback we will use to improve our approach going forward.”

The feedback—and the improvements—have already begun. This summer, at the suggestion of Stephen P. DeWeerth, the Lew and Sherry Hay Dean of Engineering, who spearheaded the FYRE initiative, nine faculty members and a handful of students participated in an accelerated, two-week workshop version of the Maker Foundations module (the first of two consecutive modules students are taking this fall). The goals were to design and build a functional machine using the same process FYRE students will experience; to introduce faculty to the equipment and resources available on campus so they could potentially incorporate them into their classes; and to gather feedback on this novel approach to teaching engineering skills.

The feedback—and the improvements—have already begun. This summer, at the suggestion of Stephen P. DeWeerth, the Lew and Sherry Hay Dean of Engineering, who spearheaded the FYRE initiative, nine faculty members and a handful of students participated in an accelerated, two-week workshop version of the Maker Foundations module (the first of two consecutive modules students are taking this fall). The goals were to design and build a functional machine using the same process FYRE students will experience; to introduce faculty to the equipment and resources available on campus so they could potentially incorporate them into their classes; and to gather feedback on this novel approach to teaching engineering skills.

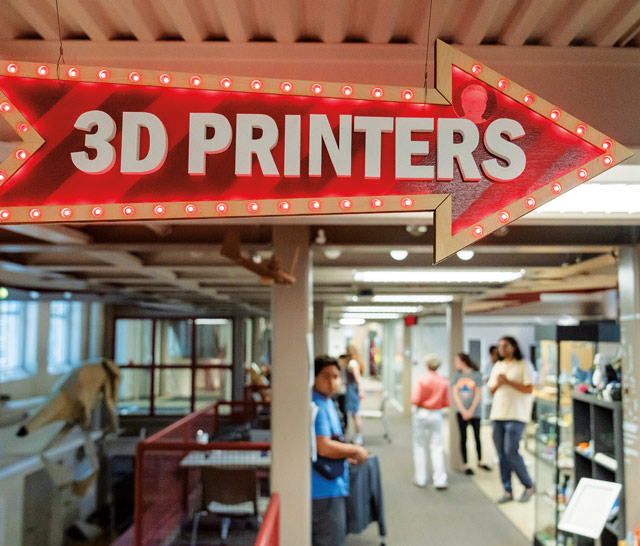

And it is indeed novel. Although these modules teach computer-assisted design (CAD) software and how to operate hardware like laser cutters and 3D printers, they also integrate subjects like math, physics, and chemistry into the creation of a tangible product.

“When I was a young engineer in college, I struggled with calculus,” says Brian Slocum, director of the Lehigh University Design Labs, who teaches the Maker Foundations module alongside Kelly Zona, manager of the Design Labs. “I never understood the point, or how it related to the real world. With all the modules we’ll be using in FYRE, we want to bring in that application piece so students see the value behind the theory.”

A few of the undergraduates currently taking part in the Maker module pilot had some existing knowledge of the software and hardware, math and physics, and programming involved in making a machine. But many of them knew nothing at all, which spurred excitement, but also some intimidation. For many of the faculty this summer, that’s exactly how it felt.

“I was a bit overwhelmed,” says Kristen Jellison, a professor of civil and environmental engineering and the college’s associate dean for faculty development. “I felt like a first-year student. I came in with no knowledge of what I needed to do to build a machine. I felt confused and unprepared.”

Jellison paired up with Susan Perry, full teaching professor in the Department of Bioengineering and the college’s assistant dean for academic affairs, over the two-week workshop. She, too, felt somewhat floored by the task before them.

“While I’ve asked my students to do CAD design and 3D printing and different types of fabrication, and I understand what the components do and what their capabilities are, I had no hands-on experience building a machine,” says Perry. “It was eye-opening—frustrating, overwhelming, exciting, and satisfying all at once."

During the first week, Slocum taught CAD, a visual thinking tool that allows the user to see complex geometries or ideas in three-dimensional space. The instructors walked through programming the laser cutter to generate prototypes of those ideas. Participants learned how to operate the 3D printer, as well as the basics of soldering, circuit design, breadboarding (a way of testing electronic circuits), and Arduino, an open-source electronics platform that allows users to create and program interactive objects.

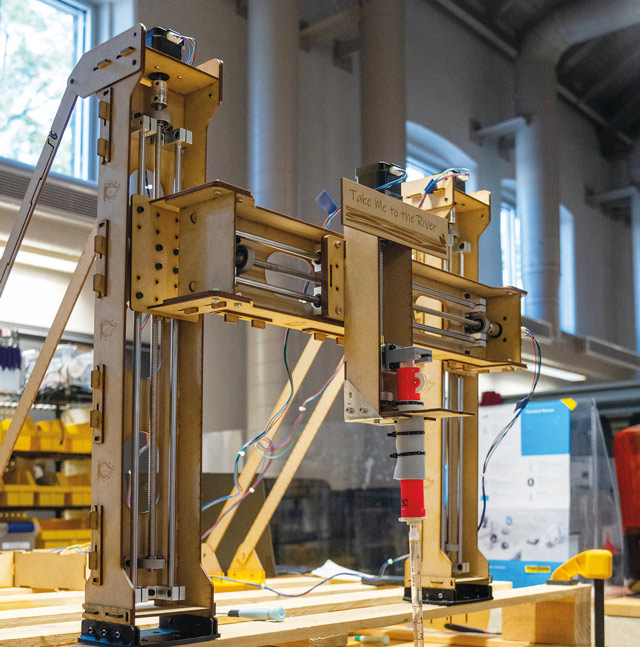

“In week two, they tied all those concepts together as they tried to solve an engineering problem,” says Slocum. “They had to come up with a design, test that design, and make their machine move in three-dimensional space and do what they wanted it to do. It was a big challenge, especially in that condensed period of time.”

“In week two, they tied all those concepts together as they tried to solve an engineering problem,” says Slocum. “They had to come up with a design, test that design, and make their machine move in three-dimensional space and do what they wanted it to do. It was a big challenge, especially in that condensed period of time.”

But it was okay to mess up, he told them, and okay to have multiple iterations in pursuit of a vision, which for Jellison and Perry was an automated water sampler.

“I cut nine versions of the box that held our pipette before I got it right,” says Jellison. “Every time I printed it out, the holes were in the wrong place or the wrong size. The thickness was wrong. At first, I was uncertain and asked a lot of questions, but by the end, I felt much more confident with the design software. Failure just became part of the process.”

The information in that first week came fast, with much of it delivered verbally. Participants quickly realized what type of learner they are.

“I’m not a great auditory processor,” says Perry. “There was a gap between listening, watching, and doing for me. I definitely struggled, and failed, early on. Kristen made nine versions, and I couldn’t even get my first box to print.”

But by the final day, the duo had a working device. Their water sampler moved a pipette to a beaker of water, dropped it down, drew water into the pipette, then raised it and moved it to a collection tube where the pipette again lowered, dispensed half the volume of water in one tube, and the other half in a second tube. They programmed it to repeat the action to minimize the need for human interaction. Ultimately, they envision an automated device that could take samples over the course of a storm, drawing and dispensing every 15 minutes from a lake or river to provide insight into the composition of water over the lifetime of a storm.

“Their experience over these two weeks mimics the one that many, if not most, students will have with the Maker module,” says Slocum. “There will be problems, frustrations, failures, but then these incremental successes will start to build and get them over each hurdle until they’ve assembled this machine they previously couldn’t have imagined creating.”

Slocum received valuable feedback that he’s incorporating this fall. He’s adjusting the pace at which he teaches CAD, and augmenting his instruction with PDFs, videos, and homework to accommodate different learning styles. The team is also adding more programming and computer science to expand project possibilities.

For Jellison and Perry, the work-shop reinforced valuable perspectives on behalf of their students. For example, learning something new is hard enough, but when you layer on being away from home (often for the first time), adjusting to college life, making new friends, and balancing a heavy academic workload, stress can snowball fast. As part of her feedback, Perry suggested that faculty devise a daily method to gauge their students’ comfort level with the material.

“If I know how they’re feeling at the end of the day, I can adjust my delivery, pace, or other parameters,” she says. “As an educator, it’s my responsibility to iterate my teaching machine.”

Jellison says that although she has always told her students that having trouble with something doesn’t mean they’re not going to make great engineers, her most challenging moments during the workshop made her realize just how important that message truly is—and how often she needs to deliver it. And so she’s keeping every piece from her nine failed printing attempts in her self-described “box of frustration.”

“It’s going to be a talking point with my students,” she says. “When they’re struggling, I’m going to pull that box out and say, ‘Do you see how many versions I had to print out?’ That’s what engineering is. You make mistakes, and that’s okay. It doesn’t mean you’re not cut out to be an engineer. We learn from those mistakes. I knew that intellectually, but I had to experience those mistakes to remember how important that message is. And by the end of this workshop, I was really proud of what we did, and felt empowered.”

“It’s going to be a talking point with my students,” she says. “When they’re struggling, I’m going to pull that box out and say, ‘Do you see how many versions I had to print out?’ That’s what engineering is. You make mistakes, and that’s okay. It doesn’t mean you’re not cut out to be an engineer. We learn from those mistakes. I knew that intellectually, but I had to experience those mistakes to remember how important that message is. And by the end of this workshop, I was really proud of what we did, and felt empowered.”

For Perry, the end of the workshop brought a renewed faith in her problem-solving skills. “The challenge of finding a solution to the problem was so fun,” she says. “Whether it was figuring out how to reconfigure our box, or how to create a different force pattern to brace our machine, I enjoyed evaluating the scenario, and working with my teammate and the others around us to take my ideas about a solution to reality.”

Perry tapped into that reinvigorated confidence when a part on her kayak recently broke. Her friend suggested that she buy a replacement online. “I looked at the part, and thought, I bet I can 3D print this”—a sentiment she would not have expressed prior to the workshop.

It’s exactly that kind of self-discovery that FYRE was designed to instill in students. That sense of wonder, joy, and excitement in finding a niche as an engineer. This first cohort of students will be trailblazers as they move through the four modules over this academic year. Their experience will further refine and strengthen a new approach that seeks to build the engineering mindset from day one.

“FYRE will enable our students to be better prepared when they leave Lehigh,” says Slocum. “Not only will they be better learners while they’re here, but they’ll have greater outcomes after they leave. We’re redefining engineering education because the world is changing. We have to change with it, and FYRE is our opportunity to do that.”