When it comes to addressing the future energy needs of the country, the best approach is a comprehensive one. The energy sector is the largest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions, but it also holds the key to get us to net-zero emissions by 2050.

“It requires all hands on deck,” says Carlos Romero, a research full professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering and Mechanics. “If we want to achieve energy independence, we need to explore innovative technologies around both renewables and fossil fuels.”

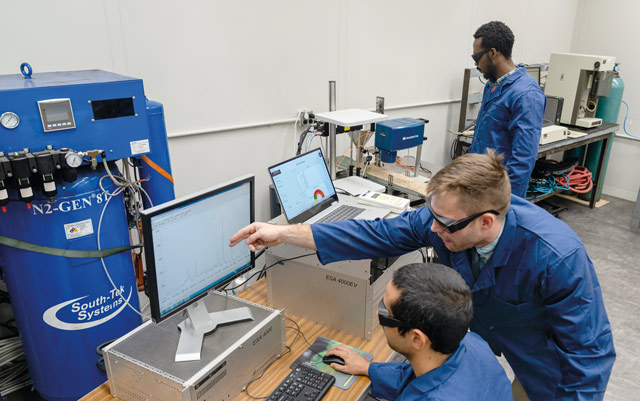

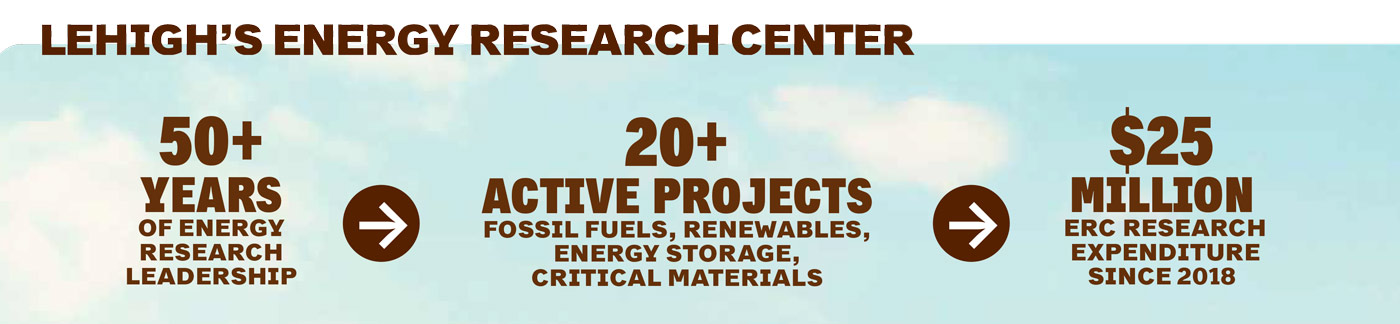

As director of Lehigh’s Energy Research Center (ERC), Romero currently oversees nearly two dozen projects and more than $3 million in research expenditures annually, spanning the continuum between conventional power generation and a cleaner, more sustainable, and cost-effective energy future. While renewables may seem the obvious path, Romero stresses that research on conventional power generation must continue and progress.

“The fossil fuels we are currently using, we’ll be using in innovative ways,” he says. “For example, putting a carbon capture system in a coal-fired power plant could potentially capture 95 percent of the carbon, and the plant could continue operating with a much lower contribution to climate-warming emissions.”

“The fossil fuels we are currently using, we’ll be using in innovative ways,” he says. “For example, putting a carbon capture system in a coal-fired power plant could potentially capture 95 percent of the carbon, and the plant could continue operating with a much lower contribution to climate-warming emissions.”

Since 1972, the ERC has been on the leading edge of innovative research into solutions to national and global energy challenges and related problems. Researchers at the center collaborate with agencies at every level of government, as well as with industry leaders, technology developers and suppliers, research labs, and other academic institutions, both in the U.S. and abroad. Within Lehigh, faculty and staff collaborate on research and educational opportunities for students. In its early days, the center was dedicated to solving problems for the power generation industry. Its agenda has since evolved—and diversified.

“Today, the center also focuses on advancing cleaner, sustainable energy solutions that benefit industry and society with cost-effective technologies,” says Romero. “We address complex, multidimensional problems by supporting partnerships with academic researchers, industry consortiums, energy firms, and government agencies with cutting-edge research testbeds and education. And we help society by reducing environmental impact and promoting energy independence.”

The ERC is advancing the energy transition on multiple fronts, including the recovery of rare earth elements, the integration of artificial intelligence in energy systems, and the development of energy storage—what Romero calls the “holy grail” of renewable energy. They are making measurable progress, yet he stresses that achieving a sustainable energy future will take a long time. It took more than a century, after all, to get to where we are today.

The ERC is advancing the energy transition on multiple fronts, including the recovery of rare earth elements, the integration of artificial intelligence in energy systems, and the development of energy storage—what Romero calls the “holy grail” of renewable energy. They are making measurable progress, yet he stresses that achieving a sustainable energy future will take a long time. It took more than a century, after all, to get to where we are today.

“We built an entire infrastructure around fossil fuels,” he says. “You can’t flip a switch and say you don’t want to use oil or coal or gas anymore, and just eliminate millions of miles of pipeline in the U.S. Consider the argument that many people cite for not buying electric cars: They say there aren’t enough charging stations. The infrastructure for that future is nowhere near as developed, and it will take many decades and a lot of investment to make it happen.”

Acknowledging that reality, the ERC operates on both tracks by advancing technologies for fossil fuels and renewables.

“We have a large sponsor base that operates fossil fuel–based assets,” he says. “We believe that those assets are a bridge to a sustainable future, and that our role should be facilitating that connection in the most environmentally responsible and efficient way possible.”

With 20-plus projects underway, and many more completed, the ERC’s portfolio is broad and emblematic of the creative problem-solving needed for such a monumental shift.

“Energy is an exciting field,” says Romero. “And there is a huge transformation happening right in front of us—from the way we generate power to the way we harvest and store energy, and how we secure the supply chains for critical materials. At Lehigh, we’re at the forefront of these critical areas.”

Improving technologies for power generation and decarbonization

ERC researchers have long investigated ways to improve power plant operations. One path involves mitigating the emissions of mercury, a neurotoxin that can accumulate, especially in aquatic systems, and enter the food chain. ERC teams have worked on instrumentation to measure mercury levels, optimized operations to reduce its production, and developed sorbents to capture it.

“Mercury is naturally found in coal,” says Romero, “which means coal-fired power plants are one of the major emission sources. But it’s a difficult element to capture because it’s released in very small concentrations.”

The team devised a novel approach of activating anthracite coal both physically and chemically. When injected into the flue gas (the gas exiting the smokestack), it attaches to the mercury and prevents it from being released into the atmosphere. The sorbent reduced emissions by 95 percent.

In a separate project, ERC researchers characterized the physics behind the transformation process mercury goes through in a power plant, in particular, its interaction with air pollution control devices like wet scrubbers (which spray a liquid to remove sulfur dioxide from flue gas). They found that when mercury is oxidized—in this case, by reacting with elements like chlorine or bromine in the coal—it can be precipitated in the scrubber solution and more easily captured.

“The paper that came out of this work has been widely cited,” says Romero. “Companies like Mitsubishi have used this study to improve their own pollution control technologies, and our work has informed and enabled industry advancements and instrument development.”

Improving power plant operations is also about reducing reliance on vital resources like water.

Improving power plant operations is also about reducing reliance on vital resources like water.

“Power plants consume an enormous amount of water to absorb and carry away excess heat,” says Sudhakar Neti, an emeritus professor of mechanical engineering and mechanics and senior scientist at the ERC. Typically, that process takes place in enormous hourglass-shaped structures called wet cooling towers. Hot water from the plant enters the tower, and as the water evaporates, heat is removed. Cool water collects at the bottom of the tower, while warm moist air releases into the atmosphere.

“You often see clouds on top of these towers,” says Neti, “and that evaporation represents a significant loss of moisture, which, when you consider how many plants there are across the country, is very expensive from a resource perspective.”

One potential solution has been the use of dry cooling towers, which channel steam in pipes. Fans then blow ambient air over the pipes to cool and condense the steam, resulting in no water loss. The problem, says Neti, is that these towers are more expensive to build and less efficient in hotter climates like in the western United States where water is an increasingly scarce resource.

“If it’s 110 degrees outside, you can’t cool the steam much below that,” says Neti. “And that reduces the ability of the plant to efficiently generate electricity, especially in low-pressure turbines, which rely on very cool steam.”

In collaboration with academic and industry researchers, an ERC team has developed a cold storage method using specialized compounds to store cool nighttime air and release it during the day to help cool steam.

“We used phase-change materials, which are substances that absorb or release heat when they change state from a solid to liquid or vice versa,” he says.

At night, the (relatively) cooler air was used to freeze calcium chloride hexahydrate. As temperatures rose during the day, the material melted, which allowed it to absorb heat and keep the cooling tower operating at peak conditions. In lab experiments, the technique increases a plant’s efficiency during the hours of peak energy and prevents the power generation units from being derated, which indicates a loss of power generated by the unit.

“We’re not the first to think of cold storage, but we were the first to find the right medium for it that’s both inexpensive and nontoxic,” says Neti. “We also addressed issues around corrosion and longevity of the material to ensure it’s economical. And our method could be integrated into existing dry cooling systems.”

Innovating more reliable renewables

Innovating more reliable renewables

The holy grail of renewable energy is storage—the ability to provide reliable, consistent power when the sun won’t shine and the wind won’t blow. The ERC, working with support from the Department of Energy (DOE), has made a significant breakthrough in that area with an innovative Lehigh Thermal Battery, a modular thermal energy storage system built with engineered concrete.

“The way you store energy in concrete is to heat it up, and then when you want that energy, you cool the concrete,” says Neti. “But concrete is a very poor conductor of heat, and so the ERC innovation was using thermosiphons, or embedding tubes that contain a fluid, which moves the energy in and out of the material.”

Thermosiphons are sealed tubes (about the width of a finger and six to eight feet long) that contain a fluid that boils when heated and condenses to release heat, operating in a continuous cycle. The tubes act as superefficient thermal conductors, enabling rapid heat transfer, maintaining isothermal operation (meaning the temperature of the system remains constant), and operating independent of thermal input and output rates, which improves flexibility for varied temperature scenarios. The combination of these hybrid approaches, consisting of phase-change (liquid to vapor and back again) thermosiphons and engineered concrete is the novelty, says Neti.

Lab and field prototypes have shown high levels of efficiency in storing and retrieving energy. In tandem with Lehigh University, Romero and Neti have formed a company called Energy Storage Technologies to commercialize the Thermal Battery, as it has applications across the conventional and renewable energy industries.

The Lehigh Thermal Battery can store coal-plant heat produced during low-demand hours for use during peak demand. It can capture and repurpose low-grade waste heat into usable energy. And it could solve the reliability problem inherent in renewables—storing the energy for later dispatch so the lights come on, and stay on.

Cross-cutting technologies

Waste accumulated from power generation could be a source of metals and minerals vital for electronics, batteries, vehicles, and clean energy. ERC researchers have been developing methods across three research pillars to identify rare earth elements (REEs) and other critical materials (such as lithium), and designing technologies that could extract those elements from what’s known as coal combustion residuals (CCRs), the solid and liquid byproducts of energy production.

The first pillar was initiated about five years ago and employed a hydrometallurgical approach using supercritical carbon dioxide along with a solvent to extract REEs.

“This method was innovative in its application of supercritical carbon dioxide, which is a byproduct of carbon capture and sequestration, to extract REEs from waste coal and acid mine drainage,” says Zheng Yao, associate director and principal research scientist at the ERC. “The process was designed as a dynamic extraction system, operating continuously rather than in discrete batch modes.”

The project yielded 50 percent efficiency when it came to the recovery of REEs—meaning it captured half of what was present in the waste.

“It was an impressive result with that kind of feedstock—both the solid, meaning the waste coal, and the liquid, meaning the acid mine drainage,” says Yao. “It also gave us important insights into the potential to repurpose underutilized carbon dioxide for critical material extraction, which helped inform our next two research pillars.”

The second pillar is built around an ongoing project funded by DOE. The project has two goals: to characterize CCRs from several utility companies to better understand REE content; and to develop an electrodialytic filtration process to selectively separate and concentrate REEs.

In terms of the first goal, the better the team understands what’s being produced by the utility companies, the better they can inform them about process changes that could yield more meaningful REE byproducts.

“Every facility is unique and burns different kinds of coal, which contain different amounts and types of REEs,” he says. “Some facilities, for instance, have legacy waste. They’ve been generating power for decades, and every year they have millions of tons of fly ash that has to be disposed of in landfills. Right now, that’s considered hazardous waste, but if we can find a reasonable amount of REEs inside it, that waste could turn into a pot of gold.”

Such a discovery is only valuable if REEs can be extracted—the focus of the project’s second goal, developing a filtration technique.

“Electrodialytic filtration is a physics and chemistry process that allows us to selectively concentrate or recover an element of interest,” he says. “So far, we’ve tested three different types of membranes, and we’re getting impressive results. One test got us as close as 80 percent. Imagine a single drop of red ink in a swimming pool. Our procedure could recover 80 percent of that ink.”

The third research pillar, still in early development, explores a new direction called electrodeposition. The process uses carbon nanotubes, rather than membranes, to capture REEs. The REEs, in solution, are directly deposited onto the surface of the nanotubes, which concentrates them into solid form.

“What’s creative about our approach here is that we’ll be using anthracite coal to create these nanotubes,” says Yao.

The result would be circular: Waste coal is transformed into carbon nanotubes, which are then used to recover REEs from acid mine drainage or other coal-derived waste.

“Many coal suppliers near the anthracite region in northern Pennsylvania want to find more uses for anthracite beyond as a heating source,” says Yao. “This could be a cost-effective approach where suppliers build a system, treat their own waste, and generate revenue.”