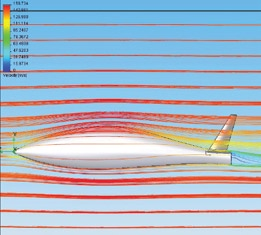

Joachim Grenestedt’s enclosed streamlined motorcycle seemed ill-suited to the rigors of racing.

The streamliner looked like a miniature airplane with no wings. To fit inside its tiny cockpit, Grenestedt, who is 6 feet 4 inches tall, had to lie almost flat on his back. After strapping safety restraints against his body, arms, ankles, knees and thighs, he could barely move his left foot to change gears. The vehicle’s low center of gravity made it wobbly at low speeds, and steering was counterintuitive: to go left, one had to first steer right, causing the streamliner to lean, and then steer left.

Last September, on the snow-white, level surface of the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah, Grenestedt raced his streamliner to a speed of 133.165 miles per hour, shattering the previous U.S. land speed record of 125.594 mph for 125-cc engines running on gasoline.

“I felt many impressions,” Grenestedt says of his dash across the desert. “New sounds, new smells, new feelings, new sights. There were too many impressions to sort out, because there was no blood running through my veins, just adrenaline.”

Speed is Grenestedt’s first engineering love. Composite materials run a close second. As a teenager, he built and raced remote-control boats. As director of Lehigh’s Composites Laboratory, he has fashioned ships, airplanes and even the deck of his house out of carbon and glass fiber composites, often in the form of sandwich structures with honeycomb or foam cores.

Composite materials, says Grenestedt, a professor of mechanical engineering and mechanics, are strong, easy to shape, resistant to corrosion and efficient. Being lightweight, they boost speed.

The Bonneville Salt Flats is home to the Bonneville Speedway and many of the world’s land speed records. Grenestedt traveled there in 2004, watched some runs and talked with drivers and engineers. After he read the rule book for land speed racing, he resolved to challenge the U.S. land speed record.

“I was looking for a new project,” he says. “I had checked into drag racing, but its rules discouraged innovation. The rules for land speed racing have stringent requirements for safety, but impose few other restrictions. I did some calculations for aerodynamic drag, power and acceleration, and I saw that it should be possible to beat a number of records without spending a fortune on engines.”

Grenestedt worked on the streamliner more than five years. Bill Maroun, a technician at Lehigh, helped with welding and accompanied him to Bonneville.

He had only a handful of opportunities to test-drive the racer.

“My first run with the bike was a few years before the race,” he says. “I had mounted the wheels, but I hadn’t yet installed the engine, brake or any other systems. I took the machine out on the street in front of our house and rolled it down a slope. My seven- and 10-year-old sons pulled on a long rope to stop me. I used training wheels to avoid falling over and damaging the fuselage.

“For my second test, I installed the engine and kept the training wheels. I really started to learn to drive the thing.”

The next run, and the last before Bonneville, came in 2008 at the Maple Grove Raceway in Mohnton, Pa. There, Grenestedt revved the engine higher and completed a quarter-mile.

Contending with salt and wind

At Bonneville, Grenestedt completed shake-down runs of 75 mph and 100 mph, and tried out the parachute brake deployment to stop the streamliner. Just before stopping, he electrically deployed two skids, one on each side of the streamliner, for the vehicle to lean on.

“This was the first time I had pulled the brake ‘chute. It felt like a gentle tug, with no hint of pulling to the side. The skids came out nicely and I was able to stop.”

On his third and final shake-down run, Grenestedt reached 122 mph while contending with two new phenomena – the slippery salt surface and a light but steady crosswind.

“The streamliner was not nearly as stable as it had been on the asphalt at Maple Grove. I had new tires for Bonneville – high-speed slicks with a round cross section – whereas I had more square tires at Maple Grove. But I think the real difference was that the salt was more slippery than the asphalt.

“I also think the slight crosswind made it feel less stable. I had to lean into the wind but steer straight, which fights natural steering.”

13,000 rpm and a new speed record

The 11-mile-long raceway at Bonneville contains a “timed mile” at its midway point. Drivers use the first five miles of the track to accelerate and the final five to slow to a stop. They repeat the process in the opposite direction, and their official time is determined by averaging the two speeds achieved over the timed mile.

“After my third trial run,” Grenestedt says, “I mounted a smaller rear sprocket to get more speed for the same engine rpm. My first run on the 11-mile course went fine. The launch was good, the acceleration good, the engine temperature was high but not dangerously so.

“It was quite exciting seeing the speed creep up to 120, 123, 125, to the record of 126 and finally to 133. By this time, the engine was revving at 13,000 rpm, well past its peak power at about 11,800 rpm. I should have been able to go quite a bit faster if I had used an even smaller rear sprocket.”

His pursuit of the land speed record, says Grenestedt, allowed him to tie together his favorite engineering themes.

“I enjoy carbon and glass fiber work, and I have a soft spot for twostroke engines. And I love cramming myself into small, fast vehicles. I wouldn’t feel comfortable driving a supersonic streamliner, but I felt great driving at the speeds I designed my streamliner for.”

Grenestedt has retired from land speed racing. He is now the adviser to Lehigh’s Land Yacht Club. Several of his students have traveled to Lake Ivanpah, a dry lake in the California desert. There, last year, they watched a land yacht set a new world record – 126 mph – for wind-powered land speed racing.

Grenestedt won’t disclose his plans. But his students have built a tire-testing rig and tried it out at Lake Ivanpah. And the club is converting an airplane glider into a high-speed land yacht.

“If I were a student today,” he says, “nothing could keep me from getting involved in a project like this.”