What happens when soldiers capture documents written in a language they don’t speak and a script they can’t read? Are the materials exploited for intelligence value or stored unread?

Too often, it is a case of too many documents and too few translators. The American military has captured several million documents in Iraq and Afghanistan, but fewer than 3 percent have been evaluated, all by humans with little help from computers.

Henry Baird and Daniel Lopresti, professors of computer science and engineering, urged DARPA several years ago to fund research to develop faster, more computerized document-analysis techniques to help intelligence agencies.

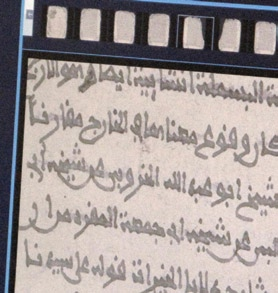

The result was the MADCAT (Multilingual Automatic Document Classification, Analysis and Translation) project, in which Baird and Lopresti participated. Its purpose was to use computers to convert foreign-language text images into English transcripts, and it has made impressive progress in recognizing Arabic handwriting.

The Lehigh team made the case for a second DARPA undertaking, the Document Analysis and Exploitation (DAE) project, recently approved by Congress. In this project, Baird, Lopresti and Prof. Hank Korth of computer science and engineering are collaborating with BBN Technologies to improve the automation of document analysis and build a national resource for shared research and access.

Optical character recognition (OCR) can identify fonts in printed documents and enable searching and editing, says Baird, but is limited mostly to Western languages on clean documents.

“You can buy OCR machines for printed text, but not for handwriting. But no technology covers, for example, Arabic or the Ethiopian languages.

“Intelligence officers might get papers in handwritten Arabic that also contain maps, tables, drawings and photographs,” says Baird. “We’d like to automate the analysis of these as well.”

“We want to go beyond written text to meta-data,” Lopresti says. “For example, if we can tell that documents appear to be written by the same author, that’s incredibly valuable information.”

Automating the analysis of documents involves scanning a document, converting images to computer-readable characters, and translating and evaluating content. Lehigh’s researchers are focusing on the second step. They will exploit synergies of document layout analysis, character recognition, language modeling and parsing, link analysis, and semantic modeling. The result will be script- and language-independent, making it easily transferable to new applications.