“When we try to pick out anything by itself,” the American naturalist John Muir wrote a century ago, “we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.”

Muir’s words are engraved on the granite floor of Lehigh’s newest academic building near a fountain of water and a 20-foot-high window. Etched into the window is an enlargement of a leaf from the American chestnut tree, the one-time canopy of eastern forests that was decimated by a fungus but is now being reintroduced. Through the glass, the stone façade of Packard Laboratory, home of Lehigh’s P.C. Rossin College of Engineering and Applied Science, appears across Packer Avenue.

Completed last summer at a cost of $62 million, the STEPS (Science, Technology, Environment, Policy and Society) building embodies the interconnectedness of life that Muir embraced and the conviction that the solutions to the world’s most pressing challenges require collaborations across multiple disciplines.

STEPS’ bold mission flows from its name. The 135,000-square-foot structure is part of an $85-million initiative that has assembled engineers, natural scientists and social scientists to tackle problems in energy and environmental sustainability that are too complex to confine to one field of study. How can changes in Earth’s climate be accurately modeled and projected? How can contaminated air and water be most effectively remediated, and clean drinking water most efficiently provided? How many factors, from government land-use policies to power transmission to the terrestrial absorption of carbon dioxide, are hitched to the desire to clear trees for a wind farm?

Lehigh’s scientists and engineers have investigated issues like these for decades. STEPS promises to enhance their efforts by fostering new partnerships among researchers who just months ago worked in different buildings. While the initiative will endow faculty chairs and student fellowships, the building will house researchers from earth and environmental sciences, environmental engineering, and energy systems engineering.

“Being under one roof,” says Derick Brown, associate professor of civil and environmental engineering and codirector of Lehigh’s Environmental Initiative (EI), “will enable all of us working on environmentally related research to interact daily. Most ideas for collaborative research come from chance meetings. You can’t plan ideas.”

Anne Meltzer, dean of the College of Arts and Sciences and professor of earth and environmental sciences, agrees.

“There are many ways to communicate over large distances,” says Meltzer, “but they don’t really substitute for working in the same building.”

The Bigger Research Picture

Lehigh’s environmental engineers and scientists are already working to improve the quality of drinking water in the developing world (see sidebar, page 14) and to remove arsenic from groundwater (sidebar, page 13). Engineers are pioneering nanotechnologies to remove toxins from groundwater and surface water (story, page 18), while journalists are studying the media’s coverage of nanotechnology’s promise and potential pitfalls.

Their new proximity in the STEPS building, researchers say, will make it possible to join forces on other areas of common interest. These include climate change, alternative energies, carbon capture and sequestration, and resource development. Graduate students in the Energy Systems Engineering Institute (stories, pages 22-23), which has also moved into the STEPS building, conduct research in these areas under the guidance of industry sponsors.

Proximity will also make it easier to address multifaceted topics. A case in point, says Frank Pazzaglia, is the management of carbon dioxide. As much as half the CO2 emitted as a result of human activity is absorbed by oceans and land surface. The myriad factors governing carbon cycling are not fully understood but are affected by forest and watershed management policies. Meanwhile, engineers are developing new technologies to capture CO2 from power plants and sequester it in underground reservoirs, while geologists are probing the behavior of those subterranean traps.

“STEPS will help us develop overarching research programs that tie together the science, technology and policy issues that underlie virtually all modern environmental issues,” says Pazzaglia, who is EI codirector and department chair of earth and environmental sciences in the College of Arts and Sciences.

“Often, the most interesting research problems lie where disciplines overlap. At these boundaries, researchers need to rely on each other’s expertise to push knowledge forward.”

A Flow of People and Ideas

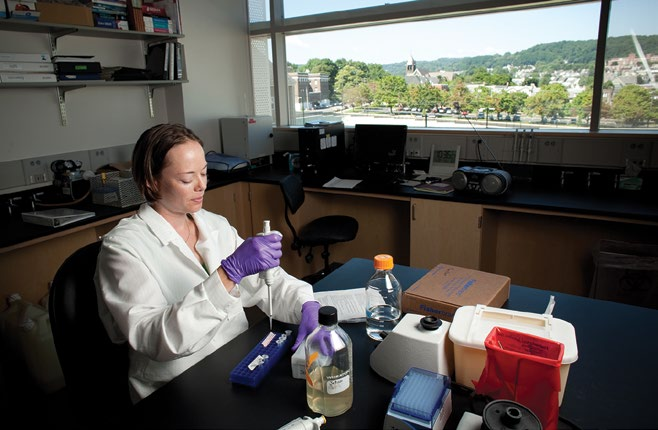

With 50 research and teaching laboratories, STEPS represents Lehigh’s largest investment in a decade in undergraduate science and engineering education. Ten teaching labs are dedicated to undergraduate courses in biological sciences and chemistry, including cell and molecular biology, genetics, integrative biology and vertebrate anatomy, as well as chemical principles and organic chemistry. The introductory courses are required of all engineering majors, and the advanced courses are required in bioengineering, chemical engineering, environmental engineering, and materials science and engineering.

The new teaching labs contain state-of-the-art instrumentation and sterilization and incubation facilities, and more seats, hood space and preparation rooms. As a result, students work in smaller teams and use more analytical methods. The hoods in the chemistry labs are made of glass, and the organic chemistry labs are equipped to do gas, liquid and infrared chromatography and mass spectrometry.

A faculty committee worked five years with Lehigh’s office of facilities services and campus planning and with two architectural firms to plan the STEPS building. Their aspiration was to design a new model for multidisciplinary collaboration in research and education, and they are confident that STEPS’ final design, by Bohlin Cywinski Jackson of Philadelphia, has succeeded.

The physical layout of the building makes it almost impossible for people not to cross paths. The administrative offices are clustered in a suite in the A wing, and faculty offices are situated along the east face of the B and C wings. Research labs are shared by multiple groups and interspersed with teaching labs and classrooms. The long concourse in the one-story A wing is ideal for poster sessions. Lounges and informal seating areas are sprinkled throughout the building and equipped with whiteboards to stimulate discussions. Those in the upper floors of the B and C wings command vistas of the Bethlehem skyline and Lehigh’s 145-year-old Packer Campus.

“The planning committee,” says Pazzaglia, “wanted to create flexible spaces that promote synergy. We put a ton of effort into designing the labs, classrooms and open spaces so that one activity would flow into another.”

A Critical Role for Glass

The junction of the B and C wings contains STEPS’ largest open space. Here the building opens into a five-story atrium whose glass curtain wall is etched with the image of a tree – roots, trunk and branches – by artist Larry Kirkland.

The judicious use of glass throughout STEPS highlights the activities of researchers and softens the boundaries between building and environment. Windows in the hallways offer views into most of the labs, while display cases lit by LED light showcase discoveries from past and present.

The glass also connects visitors with the outside environment. A floor-to-ceiling window wall runs the length of the A wing’s north face and looks onto a courtyard of native plants and grass. Faculty offices and labs are aligned east to west and have good exposure to the sun. The windows in each room feature fritted glass, vertical fins and horizontal sunshades that mitigate glare while allowing the optimum amount of sunlight to penetrate.

“The transparency,” says Tony Corallo, associate vice president for facilities services and campus planning, “helps eliminate boundaries between the inside and outside of the building. It also encourages a sense of community among the building’s occupants.”

A Good Environmental Neighbor

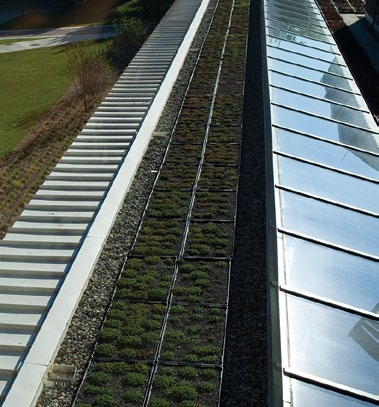

With a variety of features that minimize energy and water use while maximizing the benefit of natural light and heat, the STEPS building has been designed for silver certification by the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Green Building Rating System.

The new building also pays deference to its environment, natural and man-made. An 8,000-square-foot green roof atop the A wing retains excess storm water and releases it gradually to avoid overwhelming the city’s storm sewer system. The green roof absorbs the sun’s heat and CO2, and releases oxygen.

To reduce the environmental impact of STEPS, planners limited the A wing to a single story.

“Packard Lab across the street is four stories high,” notes Corallo. “Placing two multistory buildings on opposite sides of the same street would have created a canyon effect that we wanted to avoid. Also, as the sun traverses the southern portion of the sky, the low height of the A wing will allow more light to reach the courtyard lawn.”

Along the south face of the A wing, the planners added a wall of gray quartzite to match the iron-rich quartzite patina of many of the buildings on Lehigh’s main Asa Packer Campus.

STEPS’ overall design, says Derick Brown, is at one with its mission.

“Lehigh has long been a leader in environmental science and engineering,” says Brown. “STEPS will help us reach the next level by creating a vibrant atmosphere for interdisciplinary research and education.

“There’s a high level of excitement and activity in the new building. We’re looking forward to moving from hallway conversations to collaborative research projects that take aim at some of the grand challenges facing society.”